Anyone with two working hands and eyes can play “Celeste” and enjoy it without feeling guilty about it.

That’s remarkable.

There are games which need to be oppressive and frustrating for tonal reasons — “Dark Souls” and “Cuphead” immediately come to mind as games that would be broken if people could waltz right through them — but their difficulty comes with inaccessibility. Some people who start “Dark Souls” will never finish it. They won’t see the game’s appeal and will walk away frustrated from having had no fun.

“Celeste” is a brightly colored, redemptive and ultimately cheery game about overcoming anxiety and self-doubt. Creating those emotions in players for any extended period would defeat everything the game is about, but having no challenge whatsoever would prevent players from connecting with the game’s anxious protagonist. So instead, “Celeste” deals out however much you put into it.

On the surface, it seems like your average retro platforming challenge with modern sensibilities, similar to the 2007 PC game “I Wanna Be the Guy.” There are no enemies, special power-ups or hit points — just a jump, mid-air dash and eight massive levels on a spike-covered mountain.

The game uses a colorful and pixelated art style. (Moby Games/Courtesy)

Your goal is to get from one side of the screen to the other without dying. The average person can play the game in its normal mode and progress through its story in a matter of hours without much trouble.

However, people looking for a greater challenge can explore each level more thoroughly, take harder routes and collect optional strawberries — which are worthless, but give you bragging rights. As one of the game’s characters puts best, “Funny how we get attached to the struggle.”

Real gluttons for punishment can complete ultra-hard alternative versions of levels, known in the game as “B-Sides” and “C-Sides.” For people who would rather not deal with any of that or are new to platformers in general, there’s an “Assist Mode.” It’s clearly labeled as a non-optimal experience, and it allows players to give themselves extra dashes, skip levels and even slow down time.

“Celeste” can be super hard if you want it to be, but it can also be one of the most joyful, gentle and relaxing games you’ve ever played. Nearly every character you meet helps you along on your journey, and each of them has a voice so refreshing and modern that you don’t even notice as your “found family” builds up their support network around you.

The game has an interesting relationship with clichés. Most of them — like the aforementioned “found family” — are well-presented, but some fall flat. For example, this game has one of the best depictions of mental illness ever. Moments where the protagonist had genuine self-doubt, self-hatred and panic attacks gripped me more than any other game I've played this year. It’s candid, it’s real and it’s brutal.

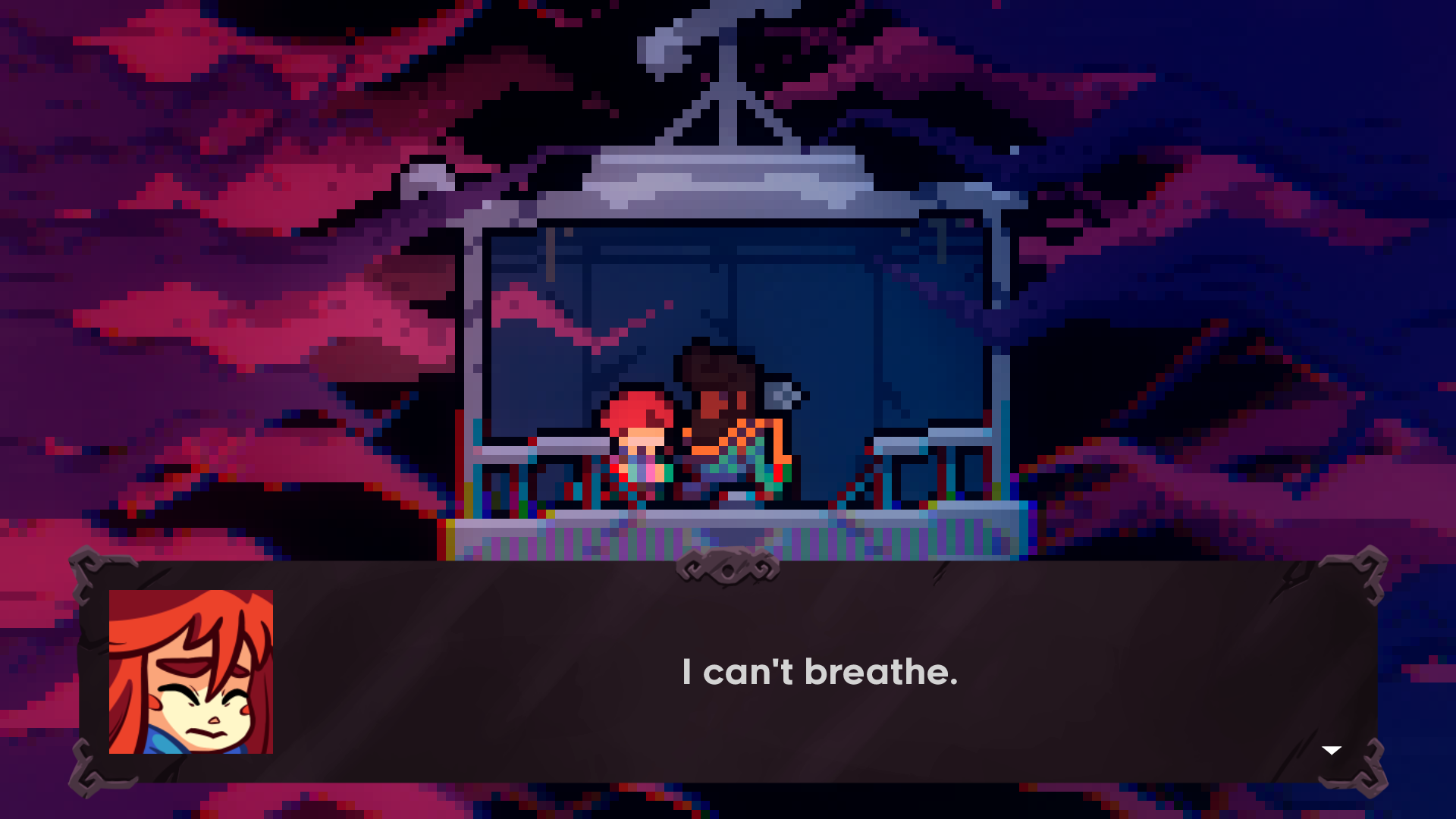

"Celeste" has one of the best depictions of mental illness in a game to date. (Wikimedia Commons/Courtesy)

This depiction is somewhat marred by sections of the game where you must literally argue with your anthropomorphized self-doubt (because magic). It goes without saying that everything about reckoning with this “other part of yourself” is a bit played out and feeds into some problematic depictions of Multiple Personality Disorder, a subject the game doesn't even try to cover.

It’s troubling because — at risk of spoilers — reconciling the relationship between you and yourself is the core of the game’s conflict, and it’s by far the worst-written part. It plays out well mechanically, as the idea of coming to terms with one’s self through cooperation over a series of difficult stages is brilliant.

Nothing forms a bond between a player and an NPC like a good challenge, and there’s no easier way to show how these two need each other than to physically make their reliance on one another essential for progression.

The question is whether this relationship should’ve been enforced in this way. The subject of the main character’s anxiety could’ve been handled through their relationship with any of the other characters without much modification, as making her internal states external doesn’t really enhance the discussion of them.

All that said, every aspect of “Celeste” is handled through such a semi-cutesy lens and with such soft-hearted sincerity, that staying mad at the game for any more than a second or two is an act of willpower.

"Staying mad at the game for any more than a second or two is an act of willpower."

It’s accessible, progressive, has good representation and is fun. There’s been nothing this cheery and interesting since 2014’s “Shovel Knight,” and even then, that title took a couple of more years to get its representation game together. If you like being happy and want a solid new indie title to play, you’ll probably like “Celeste."

Final Grade: A-