Anne Yoder, a professor of biology and evolutionary anthropology at Duke University, has worked hard over many years to give the lemurs of Madagascar an evolutionary history.

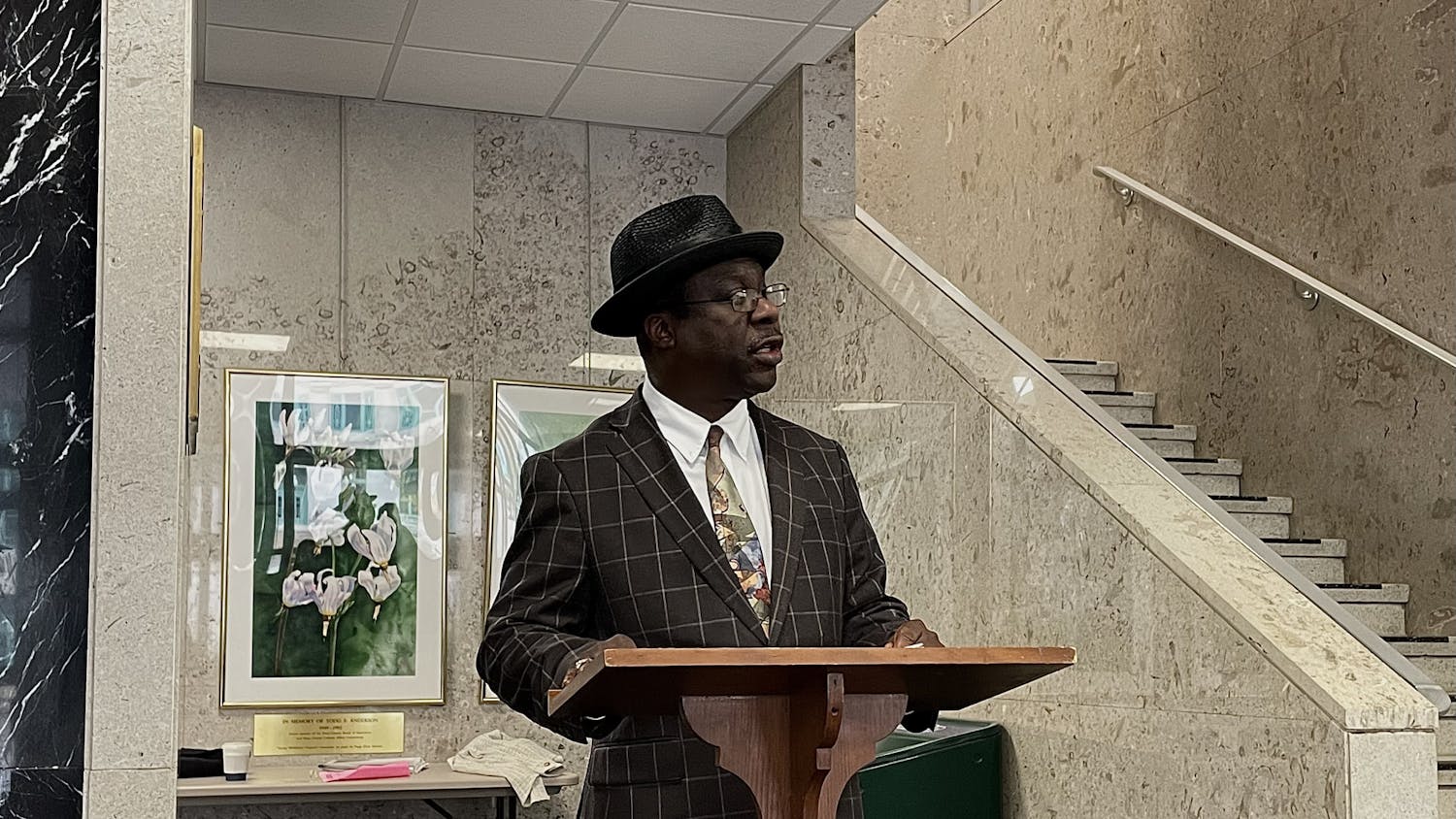

Yoder spoke passionately Thursday about her love for lemurs and the research she conducts to understand when, how and why they arrived in Madagascar many millions of years ago.

The speech, in honor of Darwin Day, narrowed in on the uncertain origin of lemurs in Madagascar, postulating several theories as to why there are many different lemur species in such a concentrated area.

Madagascar houses 20 percent of the world’s living primate species, with 90 percent of all its species being unique to the island. Madagascar is a biodiversity hot spot and is like a “speciation laboratory,” Yoder said.

This uniqueness is explained by continental drift, which isolated Madagascar 88 million years ago, according to Yoder. Though the question of how lemurs—one of the most diverse populations—colonized Madagascar after it separated from India has yet to be definitively answered.

Yoder said that sifting through several thousand strands of DNA revealed all species of lemurs in Madagascar today can be traced to one common ancestor.

Yoder expressed deep appreciation for all lemurs and enjoys studying and being around them.

“They are just… precious,” Yoder said. “They are beautiful, and they are everything.”

But climate change, deforestation and a government that oftentimes does not support ecological conservation efforts are slowly pushing lemurs out of their natural habitats. Dealing with climate change has quickly pushed them north to “keep up” with their preferred temperature, Yoder said.

The Duke Lemur Center, a research project dedicated to exploring primate behavior from a genetic standpoint, is home to around 250 lemurs that act as a genetic safety net for species of lemurs that are facing endangerment.

Yoder said the Center had at one point successfully released 13 captive-born Black and White Ruffed Lemurs into the wild in Madagascar.

She also works closely with locals in Madagascar to educate them about conserving wildlife. Yoder said she taught an intensive two-week course that showed her just how dedicated the people of Madagascar are to saving natural habitats.

“The students were so passionate and worked so hard,” Yoder said. “There’s so much raw talent and goodwill and passion to be tapped into there.”