There’s a certain paradoxical mental state most athletes try to reach when they’re in the thick of competition that seems too elementary to actually be true. When a running back is waiting for the center to snap the ball to the quarterback, a pitcher begins her windup after carefully selecting her next pitch and a hitter takes her last practice swing before stepping into the batter’s box, the last thing they want to be doing is thinking. It’s about trusting their instincts, allowing their studies of the game to become second nature and, perhaps most importantly, leaning on their set of hardened psychological skills that allow them to perform at a high level.

“So peak performers know when and how to use these and frankly, when not to and let their, as we say, to kind of get in what people call sort of the ‘zone’ or unconscious mode,” Dr. David Lacocque, a UW-Madison senior staff psychologist, said. “And that’s hard to really describe how athletes do. But there’s a quality of not thinking.”

That quality is pervasive in the minds of many Wisconsin athletes. Redshirt senior Rob Wheelwright relishes getting to that point in his game, especially given the instinctual nature of the wide receiver position.

“There’s been times in the game where I couldn’t even remember the quarterback throwing the ball and I had the ball in my hands, that’s how fast it goes,” Wheelwright said. “I’m like, ‘It just happens so fast’ and you don’t even think because there’s so much going on and it just comes natural to you.”

The importance of reaching that state of “non-thinking” within sports cannot be underscored enough. Athletes rely on it to block out distractions and allow their natural abilities and accumulated knowledge to take over, and that’s an especially difficult task to undertake at the collegiate level. With external stressors of school, social lives, an introduction to highly critical media coverage and the free-flowing information system the internet has spurred, blocking it all out and just enjoying the game has become increasingly difficult for the modern-day college athlete.

According to running backs coach John Settle, the first step in that process is preparation. He demands a great deal of focus during position meetings and in practice, issuing exams to his players covering both the offensive playbook and the corresponding defensive alignments and then paying attention to their first step during plays in practice to make sure that knowledge has been internalized.

“And the thing that we try to do in the running backs classroom, we try to take the anxiety out,” Settle said. “If there’s any anxiety that’s going to occur, anything that’s going to happen, I want it to happen in that room so when they get to the field they can cut it loose, they know that they know it, they’ve drawn it, they’ve seen it, they’ve been able to do it in front of their peers.”

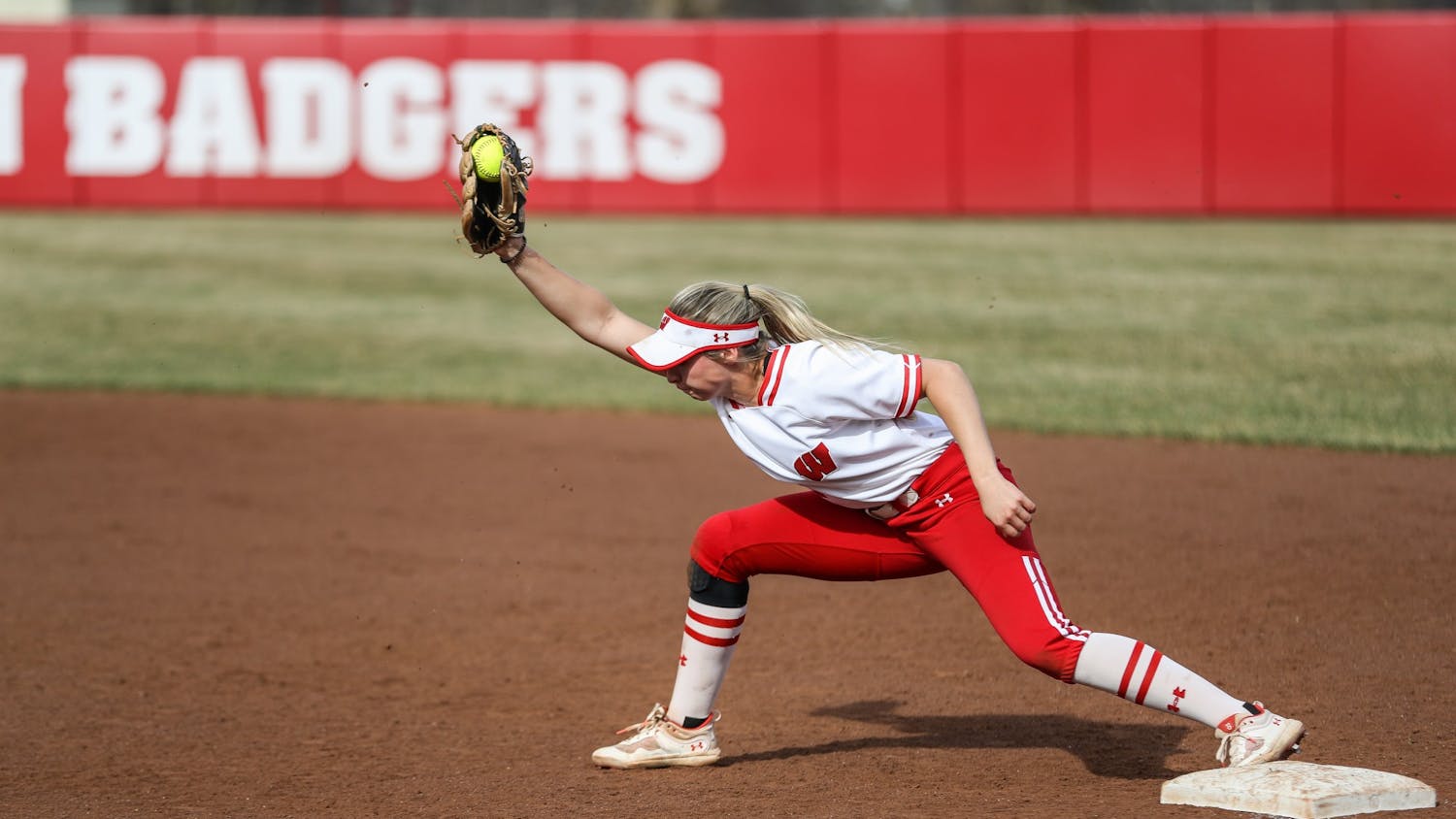

Of course, once an athlete feels comfortable with their role on the field, there are always things that get in the way. Unique to college athletes, unlike professional ones, is the impact academic performance has on their psyche. It can be difficult to compartmentalize those two factors, especially for high-performance individuals, according to Lacocque, but some, like Chloe Miller, have learned to play one off the other in a positive fashion. Her freshman season in 2013 was the hardest on her academically, but it was also the most successful season for the Badgers on the field, as they ripped off a record-breaking 13-game winning streak that spanned March and April of that year.

“When school wasn’t going the best and I knew that I was drowning a little bit and I was pretty overwhelmed with all the academic [issues] that were happening, those two hours a day where I could go spend time with my teammates and go and do the sport I’ve been passionate about for so many years … there’s nothing that can take a little stress away just like crushing the ball,” Miller said.

Difficulties in their personal lives also have a way of weaving its way into the picture. Senior running back Corey Clement, who has undergone a measure of off-the-field issues within the past few months, has become a target for fans looking to criticize his behavior, either via social media or yelling from the stands. Clement has accepted that there’s no way to escape it—he’s taken full responsibility for his actions and has made marked steps to move on, so he reflects on his football life with a broader scope in mind.

“Just tunnel vision,” Clement said. “Tunnel vision is my biggest attribute to myself. Just try to do a great job of blocking it out. Just know that those people aren’t the ones who are trying to feed your family one day in the future, and you just have to know, are they either helping you or bringing you down? Those who can help you, use them as a positive resource. If not, just leave them behind and continue on.”

Media coverage, especially with revenue sports, can start to weigh on players who haven’t quite acclimated to the type of scrutiny they can’t really control. Since running back Dare Ogunbowale made the switch to offense and started seeing increased playing time, he had to get used to both fulfilling interview obligations and hearing his name called in highlights and in rebroadcasts of games. He initially conferred with former roommate and current San Diego Charger Melvin Gordon, but the second-year NFL player shared that it’s something that athletes can never really get used to. Ogunbowale has acclimated to seeing himself on TV, but doing interviews after practices and games weighs on him.

“I would say maybe it does bug me,” Ogunbowale said. “Not in the sense of watching games on TV, but the whole interview thing. Honestly, I’d rather be in class right now than being interviewed, stuff like that, so that kind of bugs me.”

While Ogunbowale admitted talking to the media isn’t exactly his favorite activity with a twinkle in his eye, it was evident there is baggage that comes along with being an athlete that he finds perturbing.

Lacocque described student-athletes as being caught in a “unique bubble,” because their stressors differ so greatly from a typical UW-Madison student. Apart from the obvious physical demands of the game, Lacocque listed the average stressors college athletes deal with, usually on a daily basis, include handling frequent travel, mitigating internal competition with teammates, navigating an at-times tumultuous player-coach relationship, acknowledging they can’t control what’s being said in the media, both social and traditional, and maintaining relationships with friends and family. At times, this can all become overwhelming, and athletes have their own individual responses that help them deal with it. For senior pitcher Taylor-Paige Stewart, it’s all about contextualizing her situation appropriately.

“Having a bigger picture in mind—understanding that we do have less time than the other kids in our class, but we’re getting some pretty big life experiences right now and I think those are what we’re going to take from college … I think that kind of puts our mind at ease a bit too,” Stewart said.

For many college athletes, sports is as much a job as it is an escape from everyday life. It’s a time to do something they love and have worked hard at for so many years. It’s a time to leave the stressors of life behind and deal with the stressors sports provide. It’s a time to stop thinking, and start doing.