An unprecedented storm of protests resisting the Trump Administration have shocked state capitals across the country following the November presidential election—but for some in Madison, a long history of political and social movements tying back to the university have made the new wave of activism nothing but expected.

“A lot of the activism that has happened in our city has originated on the [UW-Madison] campus, whether it be during the Vietnam War or after Tony Robinson was killed or after the election,” UW-Madison professor Michael Wagner said.

Leading up to Inauguration Day, a Facebook event was launched for the Women’s March on Madison, one of hundreds of marches organized worldwide to raise awareness about women’s rights on President Donald Trump’s first full day in office.

The event, mostly publicized by social media, brought an estimated 75,000 to 100,000 people to a march up State Street. It earned one of the highest participation rates per capita in the United States and trailed only behind Washington, D.C., according to the digital strategy company Reverbal Communications.

“People often use the university as kind of a focal point to think about finding people who might want to be a part of a social movement or a protest, in planning those things and carrying them out,” Wagner said.

Wagner still questions whether activism in Madison is unique from other college towns.

“I think it’s no accident that there were larger protests in Madison than a similar sized town without a major university in it,” Wagner said. “And that’s true in other college campuses around the country, like Berkeley.”

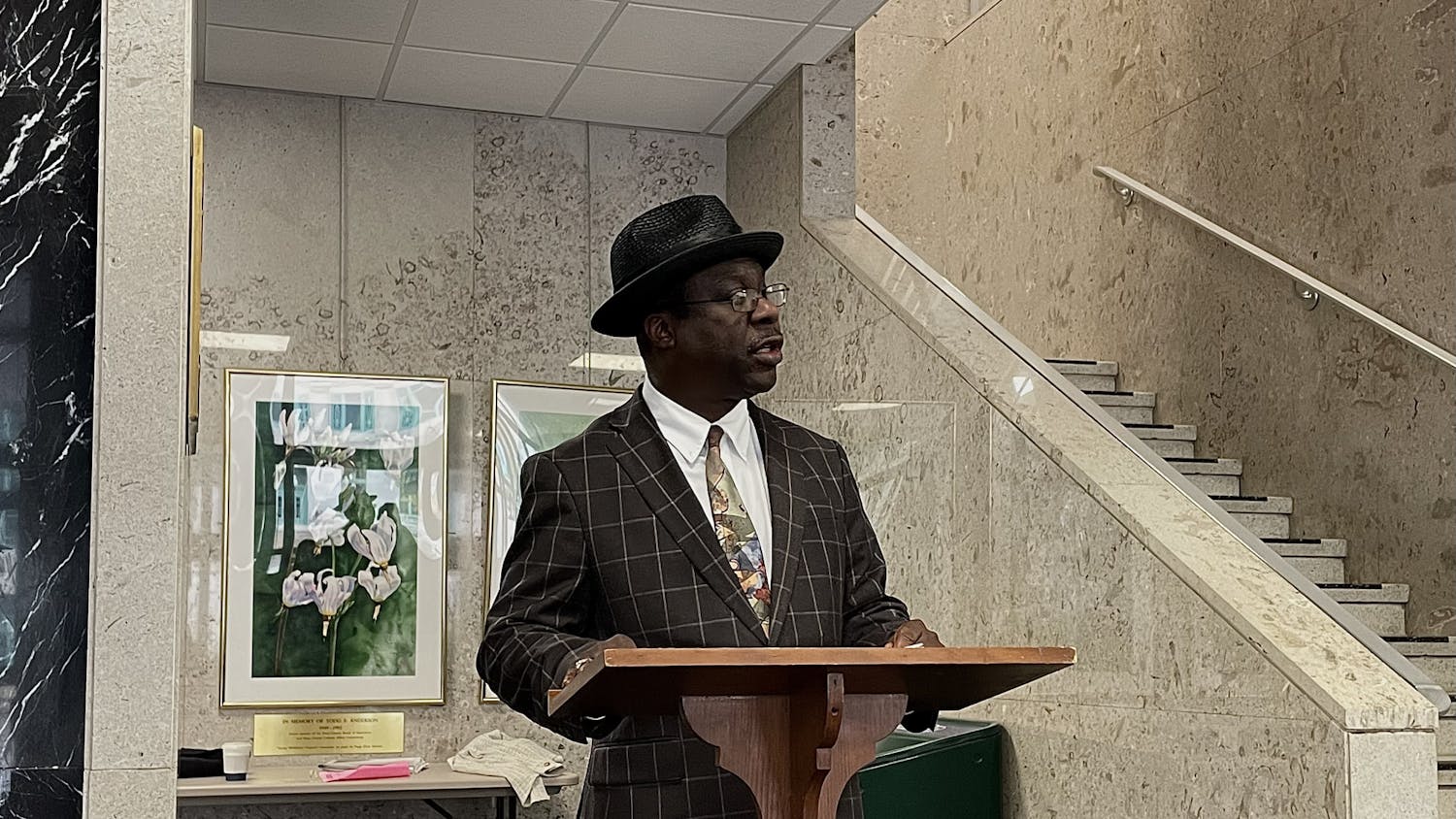

Reflecting on his own participation in protests while a student during the 1960s and 1970s, Madison Mayor Paul Soglin said the university fosters a type of activism within the city that is very distinct from other college towns across the country.

“U.S. students have historically been less active than students in [other countries]; they have been relatively quiet,” Soglin said. “But [UW-Madison] was an exception. University students and workers have had a lot to say about shaping their nation’s future.”

Soglin became involved the civil rights movement in 1962, the year he arrived on campus, as he was elected to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. He was later involved in rallies opposing the Vietnam War and the Dow Chemical Company, which he ultimately led in later movements.

“Political activity was as much a part of campus life as was going to class and studying,” Soglin said. “One thing that hasn’t changed—that unfortunately, the activism ebbs and flows in reaction to bad things.”

What makes activism on the UW-Madison campus unique, Soglin said, is one of the university’s core philosophies, the Wisconsin Idea.

“UW-Madison has had a long history of participating in the lives of the people of the state,” Soglin said. “It goes back to the notion that the boundaries of the university are the boundaries of the state of Wisconsin.”

Though notable protests on campus, like those opposing the Vietnam War, have been seen as filling a Democratic agenda, activism in the city has reached both sides of the aisle.

State Rep. André Jacque, R-De Pere, said he set off for college with plans to pursue a medical career, but his interests shifted to politics after he got to Madison.

“What [my career path] came down to was going to UW-Madison,” Jacque said. “Having the Capitol at the other end of State Street gave me an outlet … it has always been a politically active campus. There's a lot going on and that’s a positive thing.”

Jacque was active in several anti-abortion organizations and served as president of a campus chapter of the Pro-Life Action League during his time as a student.

“At a university like UW-Madison, it might be harder to find groups, activism and beliefs on the right side of the political spectrum, but it certainly exists if you look for it,” Jacque said. “It’s a large enough university that there is interest in the broad spectrum of political ideas.”

A smaller pool of conservative groups at the university, Jacque said, sometimes made for more interesting classroom dialogue.

“Not all groups are going to feel like their message is met with the same amount of acceptance,” Jacque said. “But in my time at UW, I had a number of professors that appreciated they had me on campus so they didn’t have to play the devil’s advocate in different discussions.”

Jacque said his colleagues from both sides of the state Legislature should respect political engagement by the public.

“We should have a healthy respect for activism and people who get involved,” Jacque said. “You have people who want to make a difference and make change and there’s a tremendous amount of respect for that.”