Wendy Li decided to go to graduate school last year, leaving a career in Washington, D.C. to come to UW-Madison. But just months into her stint in Wisconsin, the first-year Ph.D. student knows Congress’ tax bill could alter her life dramatically.

“This plan would completely devastate my finances,” Li told a room of students and community members concerned about the bill.

Li, like other UW-Madison grad students, makes $18,000 per year. But under the bill, different versions of which passed the House and the Senate, she’d be taxed as if she makes roughly $50,000.

This is because her tuition, which is fully funded, would be taxed as if it was additional income under the bill. It’s a policy change that would dramatically affect “what type of person can go to grad school,” according to Don Moynihan, the director of the La Follette School of Public Affairs.

“When you’re a graduate student, you get paid a small amount of money … but you get the benefit that your tuition is paid,” Moynihan said, speaking as part of a panel alongside Li. “[If the provision becomes law], only the fairly wealthy will be able to afford to take this on.”

Li’s story echoes those of many graduate students around the country who have come out in opposition to the controversial tax. Li acknowledged that although her ability to pay for graduate school would be jeopardized under the bill, her classmates who have spouses and families would be even more affected.

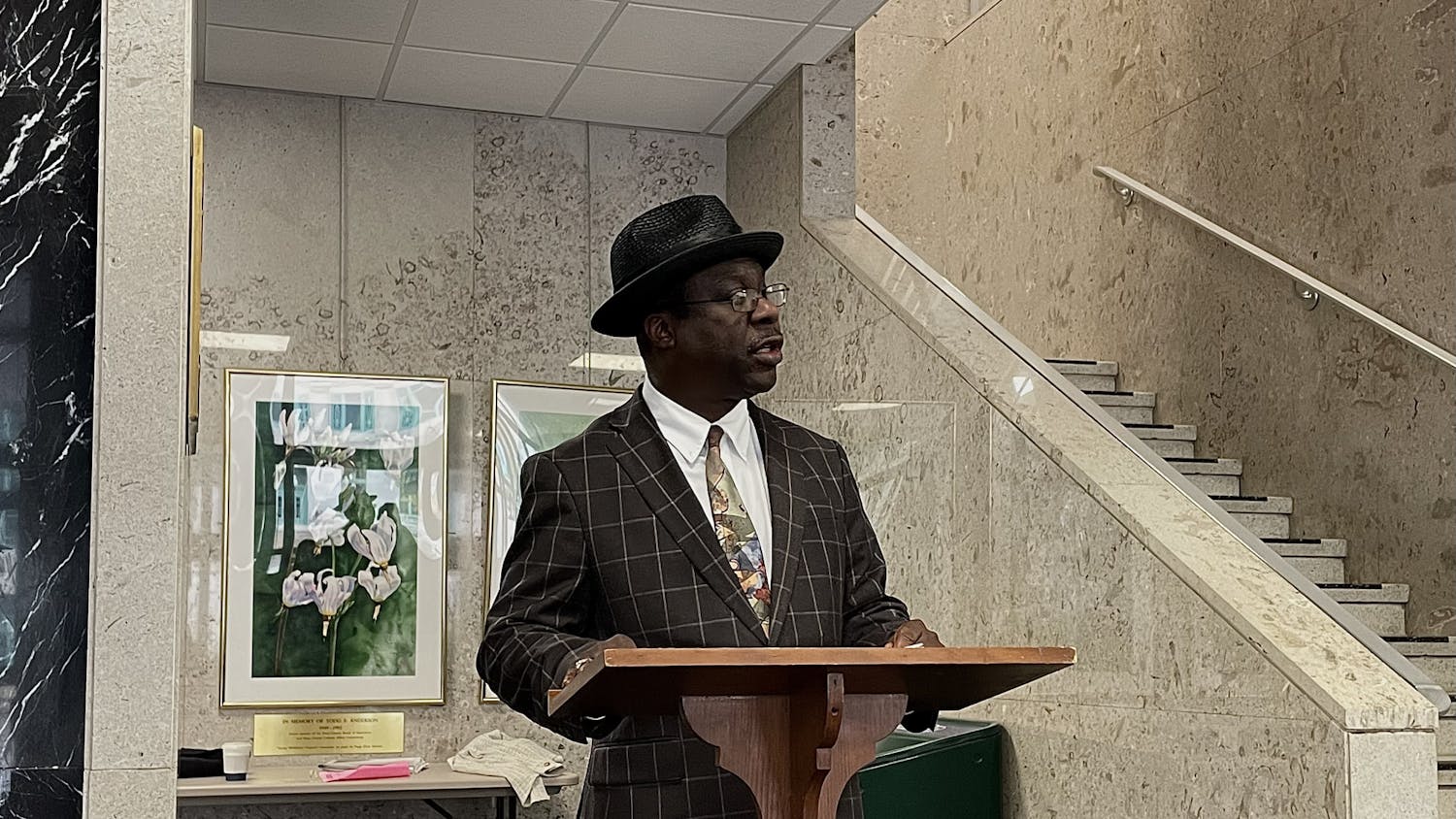

Li and Moynihan spoke as part of a panel organized by Associated Students of Madison’s Legislative Affairs Committee Wednesday night regarding the graduate student tax increase. Although some of the discussion was spent detailing the effect of the tax increase on those students, panelists stressed that the policy would impact everyone at UW-Madison.

Robert Asen, the director of graduate studies in the Communication Arts department, said because UW-Madison grad students take on teaching responsibilities, the tax increase is “an issue that has enormous impacts for undergraduates as well.”

“The brunt of these costs [from the tax bill] are absorbed by teachers themselves,” Asen said. “What happens, then, to the ability of the university to recruit teachers?”

Moynihan, who came to the U.S. from Ireland as a student, added to Asen’s point, saying the policy has the potential to especially affect American schools’ recruitment of international graduate students. Those students provide a great economic benefit to the country, he said, and may choose to go to countries like Canada if such an unfavorable tax policy is in place in the U.S.

Republicans in Congress have expressed optimism that the House and Senate will be able to reconcile the two versions of the bill and complete the overhaul of U.S. tax policy. If they do, graduate students and others on campus will start seeing the effects immediately, panelists said.

For Asen, the impact of the grad student tax increase on UW-Madison cannot be overstated.

“This affects everyone who goes to school here, and everyone who works here.”