In my experience as a journalist, I have always seen art through the lens of human connection. A single painting can have the potential to connect stories, emotions, colors and people in a room. Yet, I had never thought about the connection that modern art can lend to traditional art.

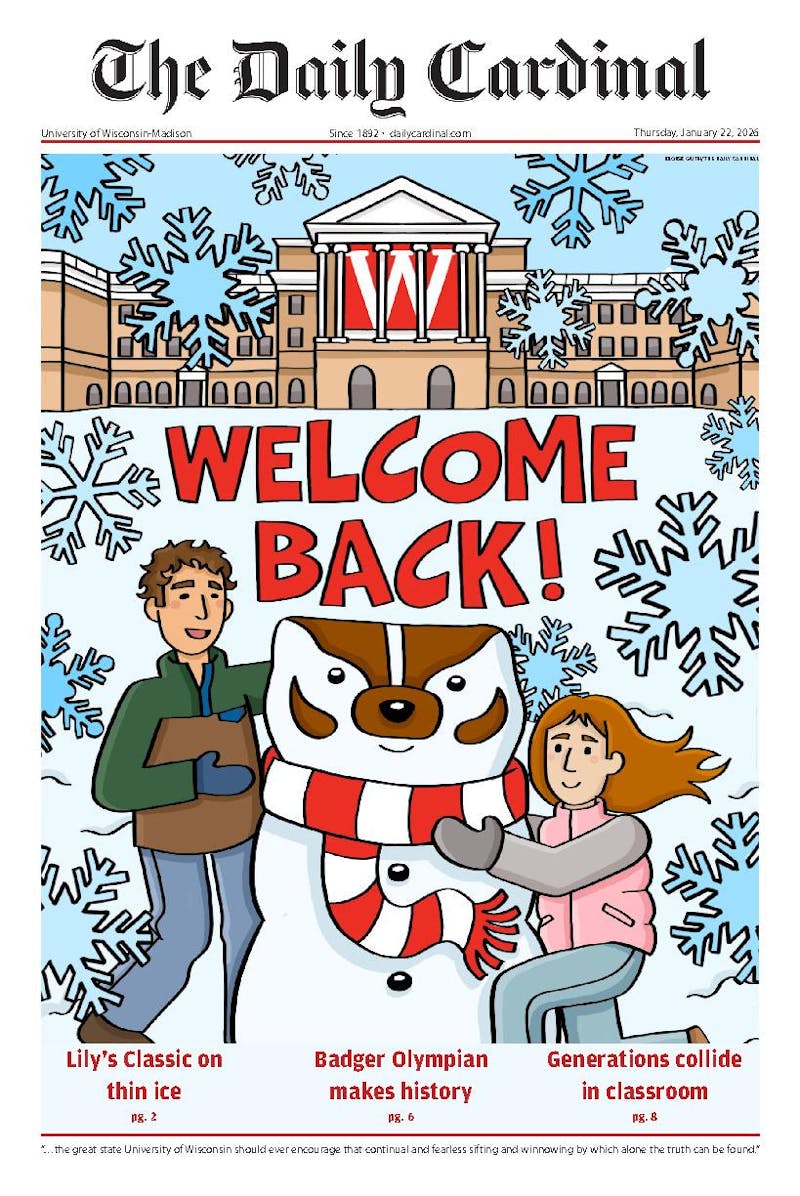

This past Saturday, the Modern Museum of Contemporary Art (MMoCA) introduced carefully curated artwork for the 2019 Wisconsin Triennial Exhibition. The gallery spoke to the accomplished and unique Wisconsin artistic community by sampling new and seasoned artists statewide. Look through these photos to learn more about the pieces and the artists themselves.

Payton Grace, from the series Strong Unrelenting Spirits (2017).

As an homage to Wisconsin’s Native American community, the MMoCA featured multiple artists who focus on tribal experience, something that was often lacking in past exhibits.

In this series, Tom Jones is recreating photographs he took of his tribe, the Ho-Chunk Nation of Wisconsin. Jones uses the Native American tradition of bead working as a metaphor for his Ho-Chunk ancestors and their spirits.

The opening of the Wisconsin Triennial attracted many from all over Wisconsin, including family and friends of the artists looking to congratulate them. Artists stood by their pieces and guests were given the rare chance to ask them about their inspiration, process and career.

Hatsubon (2016).

This series by Tomiko Jones uses multiple platforms to share a memorial of her father. She focuses on the connection between cultural landscapes and how land can shape identity and memory. The powerful simplicity of the images accompanied by the complicated emotions behind each piece created a juxtaposition that took over the gallery space. It seemed to attract many visitors to linger and reflect.

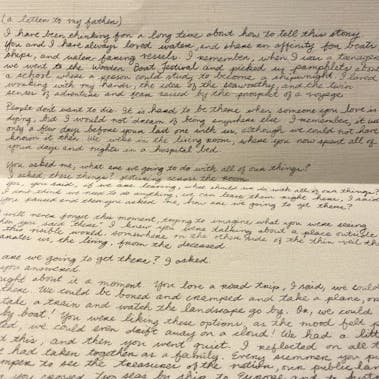

Hatsubon (2016).

This photocopied letter accompanied Jones’ work. This letter to her father was written on the one year anniversary of his death and is filled with memories and an emotional growth of Jones from the days after her father’s death to the one year mark. Her nostalgic words were laced with love and sadness that added an even greater understanding of her photos and the meaning they hold for her.

Hatsubon (2016).

The name of the work refers to the Japanese Buddhist ceremony of hatsubon. This tradition of releasing a small bamboo boat into the water marks the first anniversary of a loved one’s death.

The photos of bodies of water in Jones’ piece represent places of significance to her family including the place where her parents grew up, met and where her father was buried. It’s as though she weaves her father’s story into the land as a way to memorialize him forever.

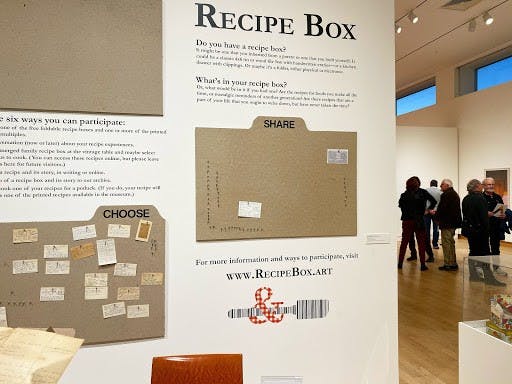

Recipe Box (2019).

Both professors at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Laurie Beth Clark and Michael Peterson focused more on performance art accompanied by installation. Their piece combined generations of recipes that they have accumulated from their own families as well as friends and neighbors.

Although the recipes were at the forefront of their piece, Peterson and Clark both said that there is something special about the way stories are intertwined with recipes. “We wanted to celebrate how people share food culture and how memory gets passed down along with it,” Peterson said.

Recipe Box (2019).

The piece includes hundreds of handwritten index cards that record decades of recipes, at times proving that it’s possible for dishes to go out of style. Peterson and Clark ask us to consider that not only memory, but also history and culture can be carried down through food.

They even took a step further by inviting guests to add their recipes to the pile while they were there. “We just saw a father sit down with his kid and write out a recipe for cookies that they make together,” Peterson said.

Recipe Box (2019).

Peterson and Clark also have a website in which recipes are being shared and conversations are being sparked. They wanted to show that the sharing and sentimentality of these recipes is just as much art as the recipes themselves.

Reading through the recipes in preparation for the exhibit was its own testament to how important the tradition of passing down recipes can be. “My mom would make liver and onions for herself when my dad left town for business bc he hated the smell,” Peterson recalled. “It’s one of my strongest memories of my mom and I just found the recipe in her handwriting.”

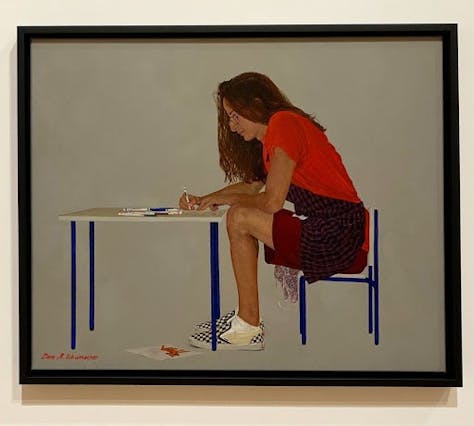

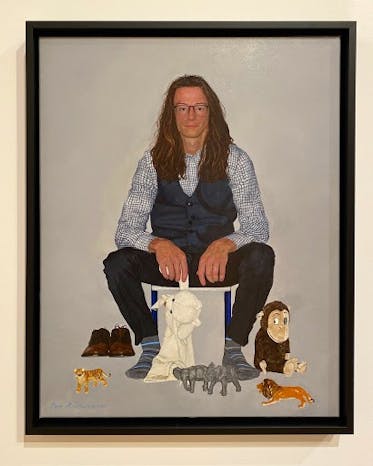

Self Taught (2018).

Dane Schumacher, still a student at UW-Green Bay, is reportedly the youngest artist to be invited to the Wisconsin Triennial. At 21 years old, Schumacher’s art reflects his youthful struggle to become an artist in the negative light that his extended family and friends have cast on him. “This was more about exploring the career of art-making and the kind of childhood imagination that I experience pursuing an art career,” Schumacher said.

Disillusioned (2018).

In this piece, Schumacher is exploring a hypothetical portrait of himself in a traditional nine-to-five career. He is much less engaged than in his other piece and is making a commentary on the life that his friends and extended family picture for him. The contrast of both pieces represent his anxiety about adulthood and how his own passions conflict with what the people around him find to be stable or practical.

“I can understand where people were coming from but these pieces show how the two paths diverge and what that might mean for me,” Schumacher said.

Self-Taught + Disillusioned (2018).

Schumacher’s family was in attendance at the opening of the exhibit. There was a contrast between his immediate family, who Schumacher said has been overwhelmingly supportive, and his extended family, who have been the more sceptic figures of his work. When asked how his extended family was handling seeing his perspective on canvas, Schumacher said, “It was a sore subject in creating the pieces and trying to talk to them about understanding that although they did have the best intentions for me, at the same time it was wearing on me.”

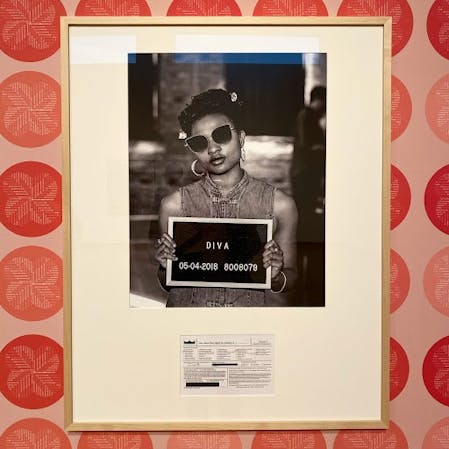

SPOOKY BOOBS (2018).

This collection of photographs, taken by Amy Cannestra, Myszka Lewis and Maggie Snyder, represent an effort to re-appropriate sexist and misogynistic language often leveled against women.

SPOOKY BOOBS (2018).

This piece shows a woman who is arrested for her behavior and given the label of a diva. In the slip under the photo, the sarcastic charges are meant to validate the behaviors and combat the label. Things such as, “Charged with speaking her mind,” or “Guilty of saying no,” are listed to further show the unfairness of these claims.

SPOOKY BOOBS (2018).

The photos are in black and white and are placed on bright, overpowering wallpaper to symbolize how the accusations have become so accepted and unnoticed in our lexicon

Xpressor 1-3.

Shane Walsh, a more seasoned artist, mainly focuses on the detailed art behind his process of making these pieces. After photocopying various marks and shakes he collects, Walsh transmits these images by hand with acrylic paint on a large canvas. Taking techniques of traditional abstraction and redefining them in the digital age shows the novelty of meeting the old and the new.

“I want that idea of the process of recombination and the remix of the history of abstraction to be apparent in the image itself,” Walsh said.

Xpressor 1-3.

Walsh compared himself to a DJ of arts, remixing historical practices and creating something new. He said that borrowing these techniques adds a layer of understanding and speaks to the artist. “I think it helps people connect to where the artist is coming from,” Walsh said.

Xpressor 3 (2016).

This close-up of one of Walsh’s pieces shows the detailed brushstrokes that are made to mimic a xerox machine.