In March, Martin Shafer, a scientist at the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene (WSLH) and UW-Madison College of Engineering, noticed a trend in COVID-19 testing techniques.

Scientists in the Netherlands and Paris had begun using wastewater-based epidemiology to paint a picture of community-wide virus levels. States including Virginia, Utah and Oregon were not far behind.

At the time, human testing was being organized but remained unavailable in most places. WSLH, though, had the expertise and molecular tools for wastewater testing in house.

“This is something that our lab, as the primary public health lab in the state, should pick up on,” Shafer thought.

Now, almost seven months later, Shafer and his team at WSLH, in collaboration with Sandra McClellan and scientists at the UW-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences, have begun sampling for SARS-CoV-2, the genetic material that causes COVID-19, at wastewater treatment facilities statewide.

“We pressed start on the program after recruiting about two-thirds [66] of the [98] facilities that we had planned on,” Shafer said.

“It’s the largest program of its type, in terms of number of facilities, in the country.”

A majority of the participating facilities have already been sent sampling supplies which workers use to “take a subsample of the sample they are already collecting.” Samples are then sent to WSLH either once or twice weekly for testing.

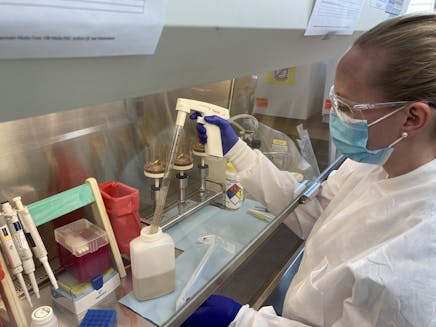

Dr. Kayley Janssen adds sewage sample to a filter. The wastewater sample will be filtered to collect the virus genetic material before testing.

“The statewide wastewater SARS-CoV-2 monitoring program covers facilities in all but five of Wisconsin’s 72 counties, including four tribal facilities, representing 60 percent of the state’s population and offering statewide geographic coverage,” wrote Kelly Tyrrell, director of University Research Communications.

While some carriers of COVID-19 never show symptoms, most shed virus into their fecal matter — which can be detected in wastewater. “Following that trend can help public health officials determine the need for further mitigation or control measures in that community,” Shafer said.

Data from on-campus monitoring has been available to UW-Madison administration since the third week in August, allowing mitigation efforts to be accessed at a multiple dormitory level.

“It [wastewater testing] certainly indicated, like the human testing did, the presence of significant levels of infected population in the dormitories.”

As for the 340-some-thousand served by Madison’s main sewage treatment facility, an integrated picture of community virus levels is being created. A surge in cases has yet to be seen among this population, according to Shafer.

The utility of the Wastewater Surveillance Program goes beyond providing early warning signals and indicating trends in virus levels. Wastewater based approaches are quite cost-effective and allow researchers to assess a larger community.

Additionally, sequencing of genetic material allows scientists to look for shifts in virus strains — shifts which could have important implications for vaccine development.

“We hope it will provide complimentary data to that of the human testing, and where there is no human testing, provide early virus warnings and tracking,” Shafer said.

Moving into the flu season and whatever the next pandemic may be, Shafer believes wastewater epidemiology will allow researchers to follow multiple viruses at the same time — providing important confirmatory and primary data.

“It offers potential well beyond the pandemic at this point,” he concluded, “there is a large team at the state lab that is dedicated to seeing this program and its significant public health benefits through.”

Funding, provided by the WSLH, UW-Milwaukee, DHS and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, totals $1.25 million and allows the statewide project to run until next June.