The gates of Camp Randall Stadium open for seven home football games every season. When they do, fans in their Badger red and white pour in by the tens of thousands.

Under a bluebird sky in 2017, another Madison resident entered the stadium. Like most, given the occasion, the visitor sported their best red and white.

This was not your typical fan though. They entered under the southwest bleachers, ticketless, and promptly took a seat in the middle of the field on the famous Motion “W.”

They were clever in landing the seat, and may have gone unnoticed, but something gave them away: they were not a badger. They were a red fox.

A fox family leaves the den to explore the UW-Madison campus.

In addition to red and white, the fox wore a tracking collar fitted by the UW Urban Canid Project (UWUCP).

The UWUCP has gained new insights about how red fox and coyote behave in the Madison urban landscape and shared this information with the public to change knowledge, opinions and dialogue surrounding urban canines.

“The project has broader implications than coyotes and foxes. If we have a healthy urban ecosystem that can support a great biodiversity of animals — including those more sensitive to urbanization — that will translate into a healthy ecosystem for human beings,” David Drake said.

The project began “serendipitously” when Drake, a professor of forest and wildlife ecology and UW-Extension wildlife specialist, was called by the Lakeshore Nature Preserve in 2014.

Staff at the preserve had been receiving comments about coyote sightings around Picnic Point — a peninsula along the south shore of Lake Mendota. Coyotes had even followed citizens who were out walking their dogs and running the trails.

Historically, literature on coyote-human encounters has been negative, Drake said. Reports detailing coyote aggression towards humans, dogs and livestock have made them one of the most persecuted animals in America.

Contrary to portrayals in folklore and popular culture, coyotes are not the cunning and malevolent characters humans have made them out to be, Drake and his team have found.

“The thing about being afraid of something is when you start becoming familiar with it you start losing your fear,” he said, capturing the project’s goal of changing perceptions through familiarity.

To get a better sense of what was going on in Madison, Drake decided to place game cameras where coyotes had been spotted. Sure enough, a pack had made the Lakeshore Nature Preserve home.

The proliferation of red fox and coyote sightings in Madison was not shocking news, Drake said. A large body of research had already been developed about urban coyotes, making any novel discoveries unlikely. Regardless, Drake jumped at the opportunity to research Madison’s canid residents.

“Nobody had looked at urban red fox in North America or the relationship between red foxes and coyotes in an urban setting,” he explained.

Early in the UWUCP, Drake and his team checked foxes and coyotes for diseases by drawing blood and swabbing the nasal and rectal passages of each animal they live-trapped.

For the most part, the animals were very healthy. They had been exposed to a variety of diseases including distemper, parvovirus and adenovirus, but a lack of data trends suggested an ability to fight them off.

“The animals are nutritionally healthy because there is so much food available and when you are nutritionally healthy, your immune system can fight off diseases,” he said. “The big difference, from a disease standpoint, was that 65 percent of the coyotes tested had lyme disease and 45 percent had heartworm. Only one fox we tested had lyme disease and none had heartworm.”

Lyme disease carrying ticks and heartworm transmitting mosquitoes inhabit the same areas as coyotes, according to Drake. The tall grasses in urban green spaces like the Arboretum and Lakeshore Nature Preserve provide suitable tick and mosquito habitat. Unlike coyotes, foxes spend their time in human developed landscapes where tick and mosquito habitat is scarce.

Drake and his team have live-captured canids and fit them with satellite collars to gather “more refined spatial data” on the animals’ whereabouts. Collars provide the researchers eight hourly locations per night on each animal.

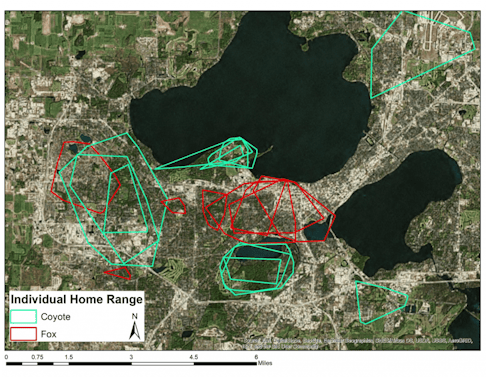

A map shows the home ranges of radio-collared foxes and coyotes in Madison.

“What we know about Madison is that red foxes and coyotes seem to be able to coexist in the same space at the same time,” Drake said.

In non-urban areas, foxes and coyotes typically overlap in habit and food type. Coyotes are about three times the size of foxes and tend to competitively exclude them. In Madison, the abundance of food means these animals do not have to compete for limited resources, according to Drake.

On mornings past, Drake has invited small groups to assist in checking the trapline and handling canids. This opportunity has given over 500 people the opportunity to have a more intimate conversation about UWUCP, learn about live-trapping and get more involved with the natural world.

“People really respond positively to wildlife. They like seeing it. It enriches people’s lives to have nature around them,” Drake said, noting tremendous public interest in the project.

While COVID-19 has put volunteering for the project on the back burner, it is not the only way to contribute. In 2015, UWUCP started an iNaturalist page where citizens could report canid sightings in the City of Madison. The data has provided a more comprehensive view than the satellite collars alone, Drake said.

The project will soon publish a paper looking at the iNaturalist data and human-coyote encounters. Each person who reported a sighting was asked to estimate the animals’ level of aggression from zero to five, with zero being least aggressive and five being the most.

“What we found in Madison, looking at 400 different first-person events, is that 97 percent were completely benign — there was no aggression on the coyotes’ part,” Drake said.

The UWUCP team has attended over 20 town hall events where they disseminated their research and provided tips for coexistence with canid neighbors.

“At all times, you need to put the fear of humans into canids. That is the best way for us to coexist. Maintaining a healthy fear of humans encourages the animals to move away from human activity rather than come to it,” Drake explained.

For Drake, sharing information about canids and promoting the positivity of their residence in Madison is among the most rewarding aspects of the UW Urban Canid Project.

Canids have strong intrinsic and utilitarian value, Drake said. They are native to the state and region, having existed here for centuries. They also do a pretty good job controlling the population of animals such as squirrels, rabbits, mice and rats, he added.

Despite hundreds of years of persecution, canids are living closer to humans than ever. The health of ecosystems depends on our ability to trade fear for familiarity and conflict for coexistence.

“The bottom line is they are here and they are not going anywhere and we are not going anywhere, so we better learn to live together unless it will be a rocky road for all of us,” Drake said.

Drake thanked the graduate students who have been “the workhorses on this project.” They have collected data and published papers, earning a bulk of the credit.

Donations to the UW Urban Canid Project can be made through the UW Foundation.