Just after the turn of the 20th century, Madison was cut in two.

It was a young city, in need of a plan to continue its growth. In the eyes of the professional class that walked the halls of the state’s capital and flagship university, Madison’s “natural advantages,” according to historian David Mollenhoff, “would make it one of the most attractive summer resorts in the country.”

Many fell in love with the isthmus’ greenery and splendid lakes. But just as important to that idyllic vision of the city were certain absences: “No soot-belching chimneys, no noisy factories and no grimy workers.”

In those early years of the city’s life, Mollenhoff writes in his book "Madison: A history of the formative years," anti-factory professionals clashed with industrialists in a debate over Madison’s character and the right to enjoy and preserve its natural beauty.

In order to placate both factions, the city chose to draw a line. They cut the city in two, creating a “factory district” on the city’s east side and a “residence district” in the west. The effects of that partition, which Mollenhoff calls the “Madison Compromise,” can still be seen today.

Quickly, the divide came to determine who could live where in the city. Wisconsin State Journal advertisement from the time sells lots on the city’s East Side as “within walking distance” of “the plants that support laboring men of the city and through them the merchants and professional men,” while land on the city’s West was boasted, in part, because “no lots [could be] sold for manufacturing, trade or commerce.”

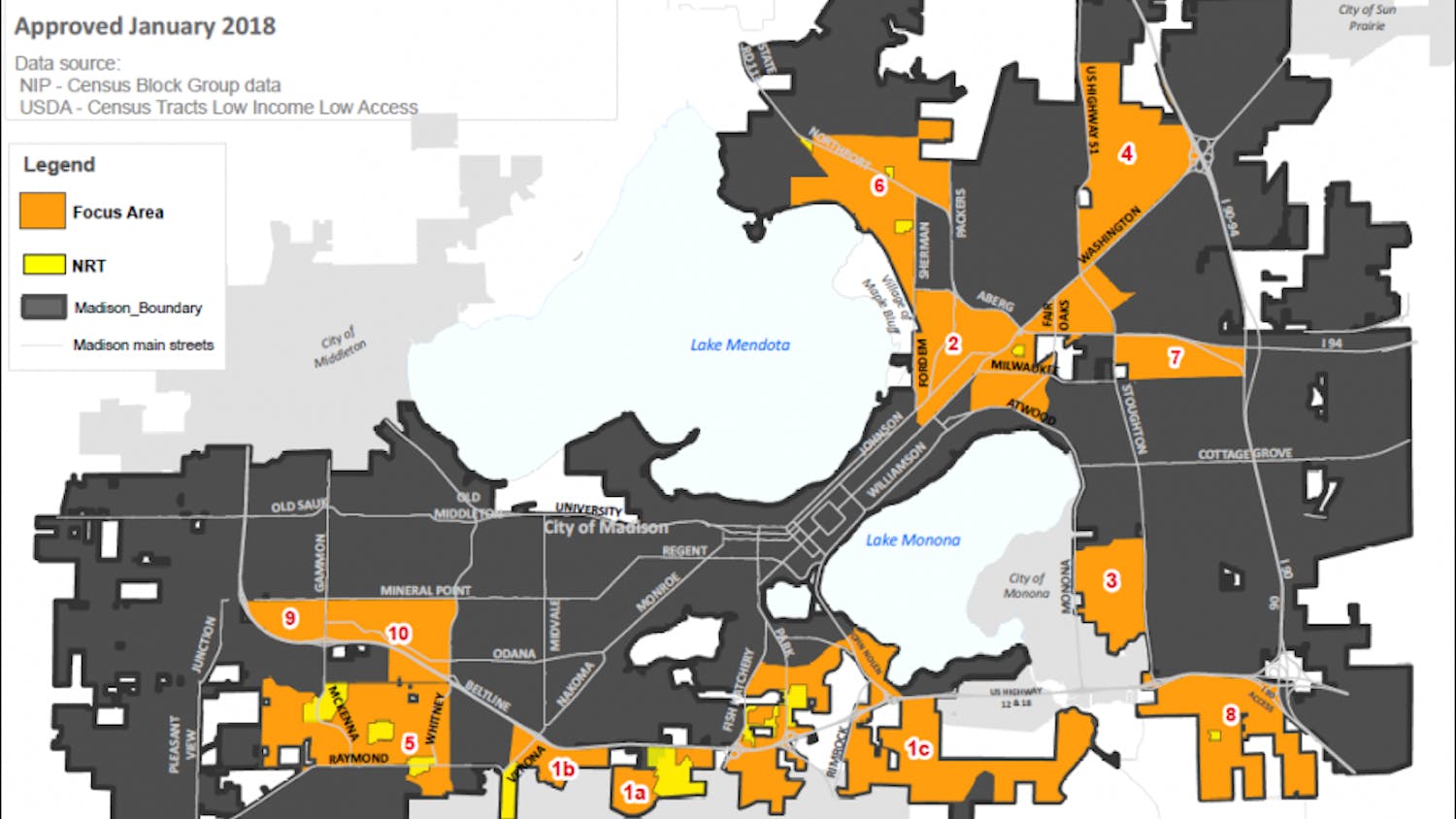

Today, neighborhoods east of the capitol and many others around the city still feel the effects of Madison’s industrial past and present. And from air quality to sound pollution to harmful chemicals in the water, it is low-income and non-white communities who are disproportionately impacted by environmental fallout.

In 1927, not long after the compromise, the city purchased 290 acres of cabbage patch to the east of Lake Mendota. In the following decades, that plot was repeatedly expanded and developed into the Dane County Regional Airport and Truax Air Force base. Today, that site is one source of harmful perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), commonly called “forever chemicals,” that in 2020 caused the state Department of Natural Resources to caution against eating some fish from the nearby lake.

The Truax base is also the prospective home to a squadron of F-35 jets, which have faced significant public opposition over their deafening takeoff sound and likely continued water pollution. Considering the makeup of nearby neighborhoods, the Air Force’s own Environmental Impact Statement for the F-35 project predicted “significant disproportionate impacts to low-income and minority populations, as well as children.” Still, in February 2020, the military chose Truax to host the jets, which will arrive in 2023.

Health risks relating to air quality throughout the city point to deep inequities in the environmental health of different communities. A 2014 report by the city’s public health department found that approximately 13 percent of Madison’s K-12 students have been diagnosed with asthma. For students who qualify for free and reduced lunch, the rate more than quadruples: 58 percent had asthma. One-third of all asthmatic students were Black, although Black students make up just 18 percent of the school district at large.

In general, Madison’s air quality is good: In the decade leading up to the 2014 report, fewer than one in one hundred days were found to have an Air Quality Index worse than “moderate.” But most of the city’s air pollution comes from vehicles and industrial sources, for which the infrastructure — major roadways and electrical plants, among others — is often closer to disadvantaged communities.

Madison Gas & Electric’s Blount Street power plant burned coal downtown for decades. Only after hundreds of residents reported worsening air quality and medical conditions did they announce in 2006 their transition to natural gas — a fuel that is cleaner but still a source of carbon dioxide. Local environmentalists later filed an unsuccessful 126-page complaint to the Environmental Protection Agency in an attempt to deny the plant a renewed operating permit.

There is also evidence that greenery in different neighborhoods can affect community health and safety. Trees improve air quality through photosynthesis, and their shade provides a cooling effect in the summer heat (which, climate projections warn us, will intensify in Madison in the coming decades). According to a DNR analysis, Madison’s east side neighborhoods appear in general to have less tree cover than neighborhoods to the west of the isthmus.

As they prepare for the looming shifts, climate scientists and policy advocates across the state are grappling with issues of environmental justice in their work.

The Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts (WICCI) recently released a report last year, which highlighted areas where “climate impacts put Black communities, tribal Nations, other communities of color and low-income communities disproportionately at risk.”

Additionally, a report by the Governor’s Task Force on Climate Change recommended the state create an Office of Environmental Justice, pointing out that many midwestern states already have similar bodies, which appoint members of communities across the state to advise on inclusive and equitable environmental policy. The report also calls for Wisconsin to improve consultation with First Nations and mandate state research on the climate impacts of racial disparities.