When I met with Charlotte Francoeur over Zoom on a sunny March afternoon, she was eager to share her experience and knowledge as a microbiology graduate student. She wore a white pantsuit patterned with red strawberries matched with burgundy framed glasses. This nature-inspired look seemed appropriate for a student dedicated to spreading the joy of natural science.

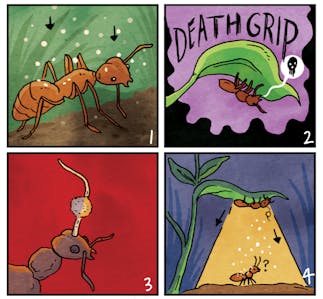

Francouer is a fifth year microbiology PhD student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She conducts research at the Currie Lab on campus where she studies microbes, which have symbiotic relationships with leaf-cutter ants. These ants make “fungus gardens” in underground chambers by bringing in leaves that the fungus degrades, and the ants then consume this fungus.

“I like to think of [the fungus garden] as the ant’s outside digestive system,” Francouer explained.

On a typical day of research before the COVID-19 pandemic, she did a mix of hands-on work in the lab with the bacteria as well as computer work, specifically bioinformatics. She also went on a few field work trips collecting insects in places including Costa Rica and the French Guiana. This past year, she has been working from home, writing her dissertation and taking part in the WIScience Fellow program. For the program, Francouer partnered with the UW-Madison Arboretum to develop an outreach project.

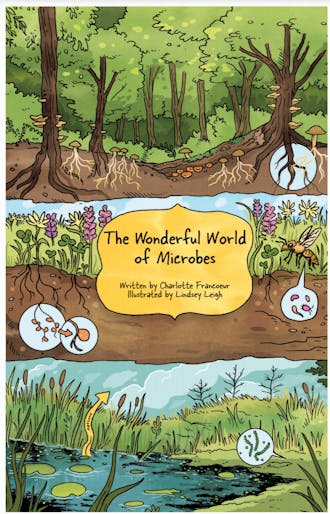

They decided to create a zine that focused on the relationship of microbes to other organisms. The zine, called “The Wonderful World of Microbes,” describes the role of microbes in everything from natural settings — insect-microbe symbioses, the leaf-cutter ants she studies and the microbes in the arboretum’s ecosystems — to how microbes can help people such as antibiotics and microbe’s functions in wastewater treatment. Francouer summarized, “when you’re learning about microbes, it feels like they’re involved in everything.”

The zine, beautifully illustrated by Linsdey Leigh, is intended to be more fun and accessible than a typical science research paper, which Francouer said almost has to be boring in order to get published. And the intended audience for the zine isn’t just other scientists — it’s anyone high school age or older interested in nature, natural science or science.

Just like the microbes she studies and their plethora of associations with other organisms, Francouer emphasized the importance of connections to grow as a scientist, including mentorship and outreach in science, because they were so important in her life. She believes that one-on-one, personal relationships are one of the best ways to learn about and become passionate about a subject.

“People are realizing that you can’t just go off in your own corner, in your own world, working on something that you never share with anyone and no one ever cares about,” Francouer said.

In high school, Francouer took a research internship at the USDA where she got to work with bacteria that they isolated from stink bugs. She credits this as a formative experience for her that set her trajectory until now. Because of this, she majored in microbiology for her undergraduate degree at the University of Maryland before beginning her PhD at UW-Madison.

When asked about her future plans, Francouer paused. “It’s funny, I’m a fifth-year [student] and I’m thinking about what to do with my life,” she said.

The one aspect of her future career she knew for certain was that mentorship will play a key role. She said that it’s an “integral part of learning about science. If I run my own lab or I’m involved in any lab environment, I want mentorship to be a big component of that.”

Francouer has been a research mentor for undergraduate student Olivia Panthofer at the Currie Lab since Panthofer freshman year. Panthofer is now a junior and is pursuing her degree in Genetics and Genomics as well as Spanish at UW-Madison.

“[We have] a really supportive relationship,” Panthofer said of her and Francouer. “It’s not just about the research; it’s about checking in on how we’re doing emotionally.”

Panthofer stated that Charlotte showed her that a huge part of scientific research is trying new things and failing over and over again until you come upon something significant. More recently, Francouer taught her to question labels and definitions used in science. For example, Charlotte explained to Panthofer that she should use the terms “isolates” or “strains” when talking about the bacteria they are working with, rather than “species,” because defining a bacterial species is controversial since they are constantly mutating

Throughout the collaborative scientific research and learning process, Francouer said, “I think when learning about the planet around us and how cool it is, you share so much joy and magnificence with people.”

According to Francouer, science can sometimes seem impersonal in complex science papers where every hint of bias and personality must be removed. However, the truth is that papers were created by people curious about the natural world, on a mission to discover more connections. Similar to how the microbes convert leaves the ants gathered into a fungus at the Currie Lab, scientists create research papers which then can be transformed into more accessible zines like Francouer’s or into dialogue between a mentor and a student to educate and inspire people.

“If I can mentor one person well and that has an impact on the choices they make, that seems really important to me, and really profound,” she said.