Going on thirteen months, the seasons of the COVID-19 pandemic have completely changed the lifestyle of Madisonians. While workforce and education have turned virtual, attention has been brought to learning new hobbies, baking banana bread and creating whipped coffee. The ability for humankind to overcome has been celebrated and the convergence of community in online forums has been articulated.

But for many, COVID-19 has caused job losses, couch surfing and bouncing rent. Although Zooming has become a second nature and glimpses into our fellow students' and coworkers' lives have added intimacy, COVID-19 has only heightened the already stark disparities for those who face homelessness in the city of Madison.

The devastation of the pandemic has widened a massive housing gap downtown, leaving students who are unable to afford the expanding luxury studios scrambling to make ends meet. With minimal support from the university, students have spent much of the semester vying for ways to meet their basic needs.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed an issue that has plagued some students for years: Homelessness.

Prior to the devastation of COVID-19, odds were stacked against students coming from low-income families. For students, the price of education is simply a fraction of the financial burden of attending a university. As UW’s Institute for Research on Poverty puts it, the “sticker price” for one year of college includes tuition, fees, books, supplies, transportation and living costs. Madison’s breakdown for just one year of in-state tuition and fees comes in at over $10,000, without considering the added fees students are responsible for.

In The Financial Barriers for College Completion, the response is simple, “as a result, low-income students can be faced with difficult financial choices. For example, tight finances among low-income students can lead them to sacrifice food and housing in order to stay in school.”

One alum reflects on his experiences becoming homeless in his final year on campus.

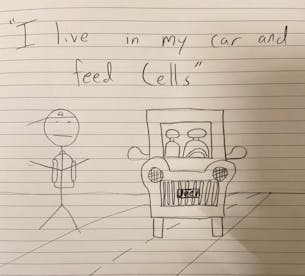

“It was hot because it was August, I would crack my windows but mosquitos would fly in and destroy me during the middle of the night,” Mark recalled. “There was one night where it was pouring all night, and it was like I was in a tin can just being pelted by the rain.”

When Mark became homeless while attending UW in 2019, he found himself living in his car. Crashing in his early 2000’s Grand Cherokee turned into a constant race against parking enforcement, as finding a place to park for a couple [of] hours — let alone somewhere off the radar for an extended period — proved to be incredibly difficult.

“I would wake up as early as I possibly could, because you could park from the hours of 6 p.m. to 7 a.m. But after that, you'll get a ticket,” Mark explained. “So I would have to wake up before that. Then I would go park in the 10 minutes zone [in] front of the Nat. I would run in, shower and brush my teeth...then I would work from like 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. and head back to my car where I’d hang out on my laptop.”

But there were times when he wasn’t so lucky. Mark got tickets three times during his time living in his car, one of which he woke up to and received in his underwear.

With astronomical rent and utility payments, the always expensive Fresh Market as the closest grocery store on campus and the University’s ever-rising “sticker price”, research does not begin to write the visceral financial burden that is felt by UW students. Social distancing has required that student dorms and apartments take the shape of the classroom, multiplying an excruciating dilemma for students unable to meet rent.

All through the semester, this concern has been echoed and amplified in ASM meetings pushing for a Student Relief Package. Up against repeated University refusal, the $2 million dollar relief fund administered through the nonprofit Tenant Relief Fund could change the lives of students facing homelessness on campus.

Blatantly speaking out against the lack of support from administration, students gathered again and again to advocate for themselves this semester.

In hours worth of open forum, students reiterated the response from the campus. Indeed, the past year had been labeled as “unprecedented times,” of which students demanded be met with unprecedented action.

“Online school is our home. Where we live is our classroom right now, this is where we're learning... what will happen to people who can't pay for housing?” said UW Senior Alex Hagen. “Quite clearly, the administration doesn't care about that at all.”

While student homelessness is now receiving acknowledgement as it is on the rise across many campuses, cases continue to be vastly underreported. For students, not having somewhere to crash can be entirely different than actually classifying themselves as being homeless. Experiencing homelessness, according to the National Center for Homeless Education, is lacking a fixed, regular and adequate nighttime residence. Falling into this category is moving from couch to couch, staying in cars nestled in the back of parking lots and spending nights in public spaces.

Many students are able to make ends meet, but according to The Hope Center for College, Community and Justice, up to half of college students attending four-year universities report housing insecurity.

For Badgers, completing a regular course load of 12-18 credits is a full time job’s worth of work. With already full schedules, students are forced to fit part time jobs into the mix. Meanwhile, Wisconsin minimum wage is only $7.25, which is far from substantial in meeting housing, utility, tuition and grocery bills.

On top of that, resources on campus for students struggling remain few and far between. For “Basic Needs,” UW provides a General Emergency Support Form funded through the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund. The university has also listed the Office of Student Financial Aid’s email address and phone numbers as well as a link to the expired application for CARES Act funds available for low-income renters in Dane County.

In addition to scarce resources, connecting students in need to these programs remains an issue.

“While I’m sure that there are resources from the university, I always just thought it was my responsibility to handle the situation,” Mark said.

The UW students who are struggling are clear in their demands: UW Administration needs to do more. Whether it be through the COVID-19 Student Relief bill or UW lead initiative, students say they need the University to stop pushing against them and help them move forward.

“[It] is absolutely 100% necessary for them to succeed academically at this institution,” UW graduate student and TAA leader Alejandra Canales stated at an ASM open forum. “For students to be attending online classes without a roof over their heads, without a stable internet connection without access to the food that they need to survive and focus and succeed is frankly really heartbreaking for me.”