As Wisconsin heads into budget season flush with $7.1 billion in surplus funds, Republican lawmakers are once again looking to reshuffle and slim down the state’s tax structure.

Citing efforts to attract higher-income people to Wisconsin and stimulate business, state Republicans are pushing a flat income tax proposal as budget negotiations draw close. Their plan would incrementally implement a flat 3.25% income tax rate across every tax bracket by 2026, ending Wisconsin’s 112-year progressive tax structure that increases taxation rates as individual income rises.

For the average taxpayer, the tax decrease would be $4,415 over the four-year phase-in period and about $1,800 per year after that. The state would foot a bill of $14.2 billion in lost tax revenue in the first four years, according to the Legislative Fiscal Bureau.

“Our state government is still taxing its citizens too much,” Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu, R-Oostburg, said at a WisPolitics forum in Madison last month. “This proposal will fundamentally transform Wisconsin’s individual income tax and keep more money in the pockets of hardworking Wisconsinites.”

Although Gov. Tony Evers called on lawmakers to return money to taxpayers during his campaign this year and signed a Republican-authored tax cut last year, the GOP’s tax proposal will likely stop at the governor’s desk. The Democratic governor previously called the flat tax a “non-starter,” instead pushing for “common ground” between tax cuts and increased shared revenue funding for Wisconsin municipalities.

"When we deliver tax relief, it should be targeted to the middle class to give working families a little breathing room — not to give big breaks to millionaires and billionaires who don't need the extra help to afford rising costs," Evers said in a Jan. 13 tweet. "That's just common sense."

Explaining Wisconsin’s income tax system

Switching to a flat tax would be a dramatic change in Wisconsin, the birthplace of the progressive state income tax system.

In 1911, Wisconsin became the first U.S. state to implement a workable progressive tax system that distinguished between income brackets, according to Wisconsin Public Radio. Though some businesses protested, the additional revenue freed the state from reliance on property taxes and allowed it to expand state services.

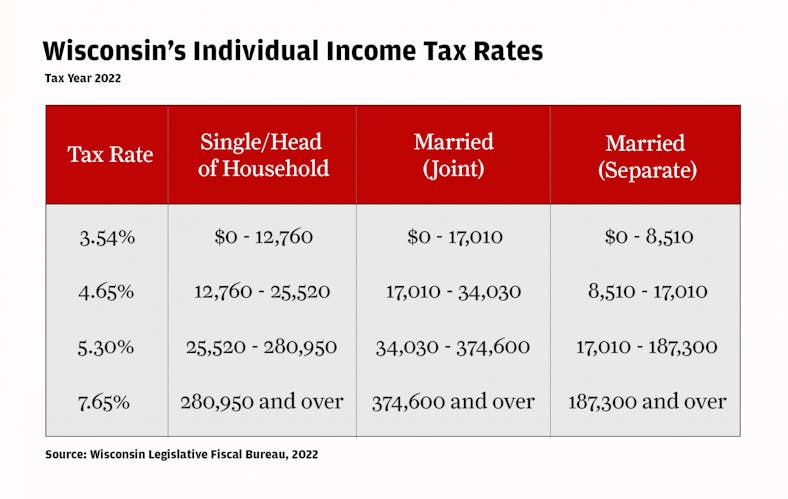

Under Wisconsin's current progressive income tax, people fall into four distinct brackets with increasing tax rates in higher income brackets.

A common misconception is that all of a person’s income is taxed at the maximum rate of their income bracket. However, only the portion of their income exceeding the prior bracket is taxed at the subsequent rate.

That means if you make $12,761, your first $12,760 is still taxed at 3.54% with only the exceeding dollar taxed at 4.65%. Under this system, any decrease in the lowest tax bracket provides tax relief to everyone regardless of income, while a tax cut for higher income brackets only relieves those with incomes at or higher than the target brackets.

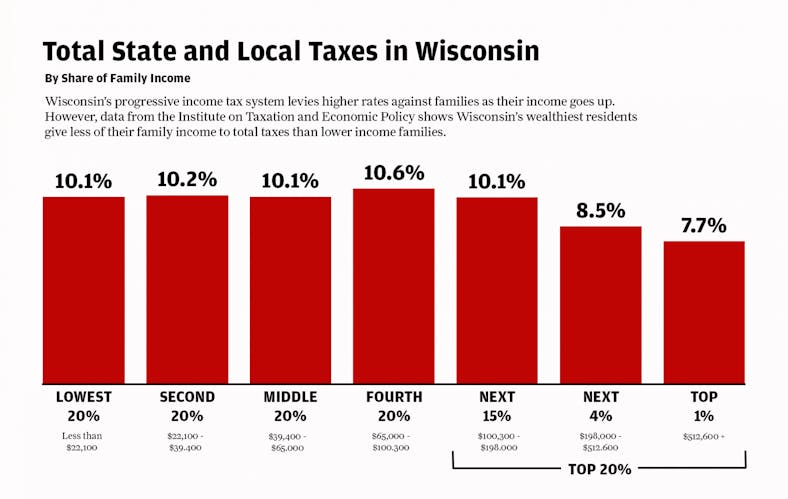

The state’s income tax has incrementally trended toward a flat tax in recent years, according to WPR. Still, Tax Foundation data shows Wisconsin ranks 13th in the nation for state and local income tax collections per capita. This said, the top 5% of households in Wisconsin actually pay the smallest portion of their income when it comes to total taxes, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP).

While most states now use a similar progressive income tax, Wisconsin stands out among its neighbors — namely Michigan, Illinois and Indiana — that use a flat tax system. Wisconsin’s tax rate for the highest bracket is also higher than these same three states’ flat tax rate.

"We're sort of an island with our top tax rate here in Wisconsin," LeMahieu said. "We need to drive that down."

Yet as some states have been moving to adopt flat taxes, others are implementing new "millionaire taxes" on their wealthiest taxpayers, according to CNBC. That’s left Wisconsin in a rift between diverging state tax schemes.

“State tax systems are moving in both directions,” University of Wisconsin-Madison Assistant Professor of Public Affairs Ross Milton told PBS Wisconsin last month. “We're seeing the adoption of millionaire taxes in other places like California and New York as well. So what's happening is more like a bifurcation of tax systems than anything else.”

What a flat tax means for Wisconsinites

LeMahieu contends a flat tax will make Wisconsin more business-friendly, calling the current tax system “uncompetitive and mediocre.”

In a memo sent to lawmakers on Jan. 13, he argued a flat tax would promote entrepreneurship and help Wisconsin businesses — 95% of which are taxed on their owners’ personal returns.

“Moving toward a flat tax with a low rate will benefit everyone — small business owners who create jobs, individuals looking to earn more or keep more, folks who aspire to start businesses themselves and would like to do it in Wisconsin,” Badger Institute President Mike Nichols said in the memo.

“Right now, we’re nowhere close to competitive,” Nichols added. “Our neighbors will be thrilled if we remain complacent. They’ll gladly steal our companies, our jobs and our tax revenue.”

Nichols’ concerns come as Wisconsin is estimated to lose 130,000 residents of prime working age by 2030 as young people leave for states with lower income taxes and warmer weather, among other reasons.

The state is simultaneously suffering a “brain drain” among its most educated residents, many of whom are college graduates leaving for bigger cities like Minneapolis and Chicago.

Proponents of the flat tax like LeMahieu argue that lowering taxes will attract higher-income residents and businesses back to Wisconsin.

“We need to be competitive to attract talent into the state, attract them to grow, start businesses, bring their families here. If you live in Kenosha, if you’re successful, why would you not move to Illinois and pay 2.5% less?” LeMahieu told the Badger Institute.

States with lower, more competitive tax systems generally have a tendency to experience inbound migration, according to the Tax Foundation.

Additional research from UW-Madison’s Center for Research on the Wisconsin Economy suggests a flat tax, when partnered with a sales tax increase, could encourage businesses to hire and households to save, improving economic output and wages. Wisconsin’s current 5.43% combined state and local sales tax rate is the fourth lowest in the nation among states that have sales taxes, according to Tax Foundation.

However, a 2016 study found that very high-income households are substantially less mobile than lower-income households. The study also found tax differences between states have minimal impact on where millionaires migrate.

“Millionaires are not searching for economic opportunity — they have found it,” researchers said in the report.

Further, U.S. interstate migration is rare in general, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. When it does occur, it’s more often driven by employment, housing affordability and cost of living concerns rather than personal income taxes.

Flax tax and inequality

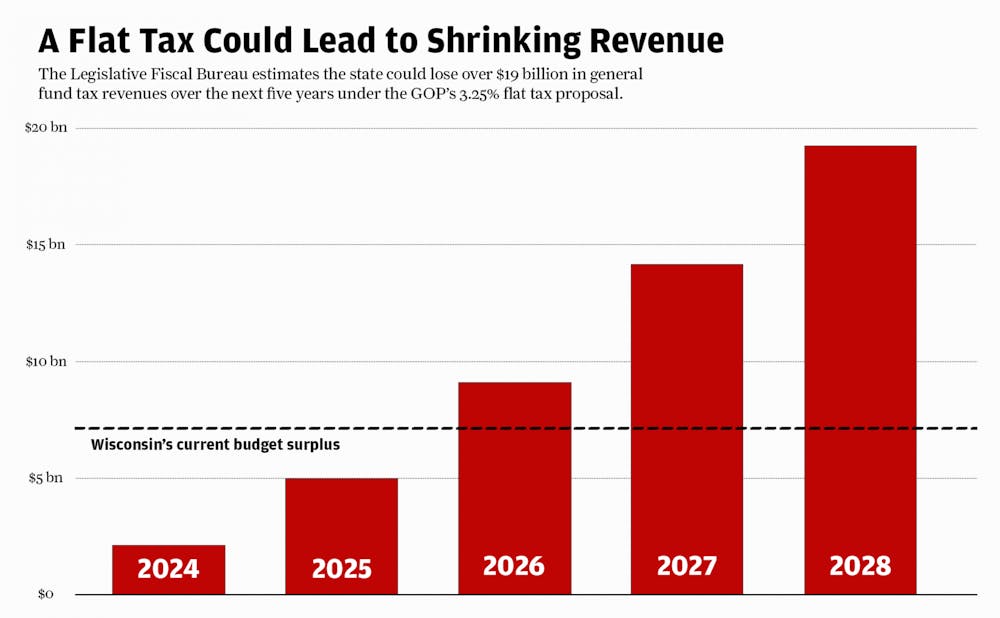

The GOP’s flat tax proposal would eliminate billions in future state funding. Wisconsin would take in approximately $14.2 billion less in tax revenue over the first four years following the adoption of Republicans’ proposed 3.25% tax rate, according to a Legislative Fiscal Bureau analysis — an amount roughly double the state’s current $7.1 billion budget surplus. Annual revenues would be reduced by about $5 billion for every subsequent year.

That amount is over half of the total K-12 school assistance in the fiscal year 2023, three times as much as the UW System’s 2023 budget and four times the amount of the total shared revenue that year that supports all county and municipal services, according to figures from the Department of Administration.

And though Wisconsin currently has a hefty budget surplus that could grow to just shy of $9.8 billion by 2025, per DOA figures, Milton said a spending reduction coupled with a flat tax could leave the state in a vulnerable financial position.

“I think that the concern that many people have about big tax cuts now is that we need to have sustainable tax policy that sets our state on a good trajectory that we will be able to maintain,” Milton said. “Not one where we're going to have wildly oscillating tax policy every few years when we realize that we cut taxes too much and our state's going bankrupt.”

If a recession hit the U.S. economy — which a study from the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center suggests is a strong possibility in 2023 due to high inflation and rising political tensions worldwide — a flat tax could leave Wisconsin and its cities short on cash.

“When you create that really low flat tax, you’re tying the hands of your revenue system,” said Richard Auxier, senior policy associate at the Tax Policy Center, explaining it may be difficult to recoup lost income during an economic downturn.

To enact a “revenue neutral” flat tax without significant spending cuts or rises in other taxes, the LFB estimates the flat tax rate would actually have to be 5.22% — an amount similar to what Republican gubernatorial candidate Tim Michels proposed last fall. But under this proposal, most Wisconsin taxpayers (72.5%) would see an average tax increase of $249 per year, with higher tax increases on the lowest incomes, according to Wisconsin Watch.

Only 2% of filers would receive tax reductions, and those earning over $1 million per year would get a tax cut of $112,000 on average, according to the LFB.

"A flat tax either raises taxes on those who can least afford it or results in massive spending cuts that hit the poor and middle class hardest – often it does both,” said Sen. Chris Larson (D-Milwaukee) in a statement to The Daily Cardinal.

Larson went on to call the flat tax “a relic of trickle-down economics from the 1980s that has been soundly rejected by the vast majority of economists.”

“If you like massive cuts to education, infrastructure, healthcare, and the environment while giving big handouts to those who need them the least, the flat tax is for you,” he said.

Wisconsin could still implement a lower flat income tax by deferring some of the revenue needs to other taxes such as sales tax or property tax, according to Urban Milwaukee.

However, this would also disproportionately affect lower- and middle-income families, who spend a higher proportion of their income on everyday expenses like groceries and housing — the types of purchases sales and property taxes target, according to the ITEP.

“When considering all state and local taxes, Wisconsin already has a regressive tax system – meaning that the more money you make, the less you pay in taxes as a percentage of your income,” Larson said, citing the ITEP. “Under the GOP flat tax, the top 1% of earners would pay less than half the percent of their income in taxes as the bottom 40%.”

Milton notes that the impact of such a flat tax on lower-income households would vary greatly on the specifications of the proposal, citing the standard deduction as an example.

“When do you start paying this flat tax rate? Is it at $5,000 in income or is it at $20,000 in income?” Milton said. “In order to make a flat tax system not dramatically increase taxes on low-income households, it would have to be accompanied by a potentially substantial increase in the size of the standard deduction.”

Budget battles ahead

Gov. Tony Evers announced his executive budget last Wednesday, which included a 10% tax cut for individuals making less than $100,000 per year and a $2.6 billion increase in funding to public schools. The governor said his new tax plan would “give families a little extra breathing room” and bolster Wisconsin’s post-pandemic workforce.

Wisconsin’s unemployment rate currently sits at 3.2% after the state added 60,000 jobs last year, according to the latest data from the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development.

“That’s real, sustainable relief that will keep income taxes low now and into the future without causing devastating cuts to priorities like public schools and public safety,” Evers said during his budget address.

Evers previously floated a $600 million plan last August that included a 10% tax cut and expanded several public services, including education and public health. But Republicans swiftly shut it down, with Assembly Speaker Robin Vos calling it a political ploy to gain votes in the November midterm elections, according to Wisconsin Public Radio.

It’s unlikely his revived tax cut proposal will appease Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, who told Wisconsin Public Radio in November that Assembly Republicans would focus on returning money that was "overpaid" by taxpayers.

"I think it's fair to say that our first priority would be cutting taxes as much as we possibly can," Vos said. "The second would be we're going to keep the money in our savings account. I would rather keep it in the savings account than expand the size of government."

Republicans on the Joint Finance Committee (JFC) already told reporters they plan to throw out Evers’ budget, which JFC co-chair Sen. Howard Marklein called a “liberal wishlist.”

There’s some hope for compromise as the budget process moves forward. Vos has previously indicated conditional support for an increase in public school funding if paired with an expansion of the state's private school choice program.

He also suggested a potential to “thread the needle” on tax cuts so long as Wisconsin’s budget surplus was going back to residents rather than into state spending, according to a November report from The Center Square.

Vos struck a similar tune last Wednesday when he told reporters there were “some areas” of common ground in Evers’ budget. However, he said Republicans’ solutions would look “dramatically different” than the governor’s “unrealistic” plans.

"In some ways, I felt like I was watching Oprah Winfrey — a billion for you, a billion for you, a billion for you," Vos said.

Alex Tan is a staff writer for the Daily Cardinal specializing in state politics coverage. Follow him on Twitter at @dxvilsavocado.