Students for Justice in Palestine and a local chapter of the Young Democratic Socialists of America organized a pro-Palestine encampment on April 29 calling for the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s “financial and social” divestment from Israel.

Lasting a total of 12 days, the encampment came to an end on May 10 after UW-Madison administrators reached an agreement with protest organizers.

This local protest took center stage in state politics, with lawmakers divided on whether the encampment was a justified use of expression and protest, or whether the university and state at large should take action to dismantle it.

Editor’s Note: This article is a report of recollections and opinions stated both in the immediate aftermath of the encampment’s closure in May, and in a series of follow-up interviews conducted in August.

Hong says encampment ‘fostered democracy,’ others say it broke law

Rep. Francesca Hong, D-Madison, saw UW-Madison’s pro-Palestine encampment as a space for civic engagement and community building during “a time of immense despair.”

To Hong, the encampment represented a separate sector of democracy beyond voting — it was a “fostered democracy.”

“We can't think of democracy as just voting,” Hong told The Daily Cardinal. “Democracy is about fostering conversation and honoring different identities and viewpoints.”

While Rep. Lisa Subeck, D-Madison, told the Cardinal she acknowledges protest is a tool for change, law and regulations remain an important principle for protesters to follow.

“You can certainly exercise your right to free speech and right to assemble without tents in a camp… there is protest and then there’s civil disobedience,” Subeck said. “Actions have consequences, so whatever it is the protest is about when they choose to set up an encampment such as these students did, there are consequences that can come with that.”

Still, Hong said state lawmakers do not do enough to embrace their constituents' concerns, as she says she was one of few elected officials to visit the encampment.

“I wish more elected officials could have experienced what the student encampments were about and had more nuanced conversations about what they represent,” Hong said.

A lack of engagement with constituents can lead to a disconnect between elected officials’ views and the needs of voters, Hong also noted.

Since Hong is the only one who directly represents voters within UW-Madison’s borders, Subeck noted in August that Hong is in a unique position compared to a majority of other representatives in the Legislature.

“My first responsibility is to the people in my district, but I recognize that every decision that we make is made in a broader context that includes our city and county,” Subeck said.

When asked whether she had the opportunity to visit the encampment, Subeck said she did, but felt that it wasn’t in the best interest of her “safety or security” to visit the encampment.

“The setting of the encampment was not a comfortable setting for me as a Jewish woman,” Subeck said. “There was enough clear antisemitism in and or around the encampment that I did not feel it was in the best interest of my safety or security to go to the encampment.”

However, Hong thinks the encampment was a place where hard conversations between those with conflicting viewpoints about the ongoing war in Israel and Palestine could be discussed in a civilized and nourishing manner.

“What I can now say about my experience with the encampment is, I know that it's possible for these conversations to be nourished. And we have to have nourishing conversations in order to show that we can make a difference in this world,” Hong said.

Some lawmakers say police raid was acceptable, Hong disagrees

On May 1, the third day of the encampment, UW-Madison Chancellor Jennifer Mnookin authorized police to remove the encampment from university property.

Hong referred to police activity on May 1 as “state-sanctioned violence.” The police raid disappointed her because it “created more chaos, and less order.”

Once Hong realized police were called, she feared immediately for the community, with her primary concern being the mental and physical safety of those gathered at the encampment.

Protesters were given 15 minutes to remove all tents and equipment before law enforcement pushed their way into the group of demonstrators, who had linked together to form a human wall around the encampment.

In the aftermath of the police raid, four protesters were booked at the county jail, two UW-Madison professors were injured — with one having to report to the hospital — and eight police officers sustained injuries related to the incident.

Now, in August, Hong looked back at the police raid as a turning point in the protest and a mistake on the part of the university.

“It further escalated tensions between the different perspectives on the genocide, and we saw that it only fueled more fear and hate,” Hong said.

Subeck and Rep. David Murphy, R-Greenville, argued in May the use of police to dismantle the encampment was wholly justified and expressed disappointment with how quickly the encampment returned.

Subeck further said the protesters who were arrested “basically played victim,” in the aftermath of their indictments.

“To say ‘I’m willing to be arrested, I'm willing to face those consequences for this cause,’ that is a decision that an individual makes, but afterward, you’re not a victim. You chose to make the statement for your cause,” Subeck said.

Antisemitic chalkings left Subeck and Murphy worried about safety

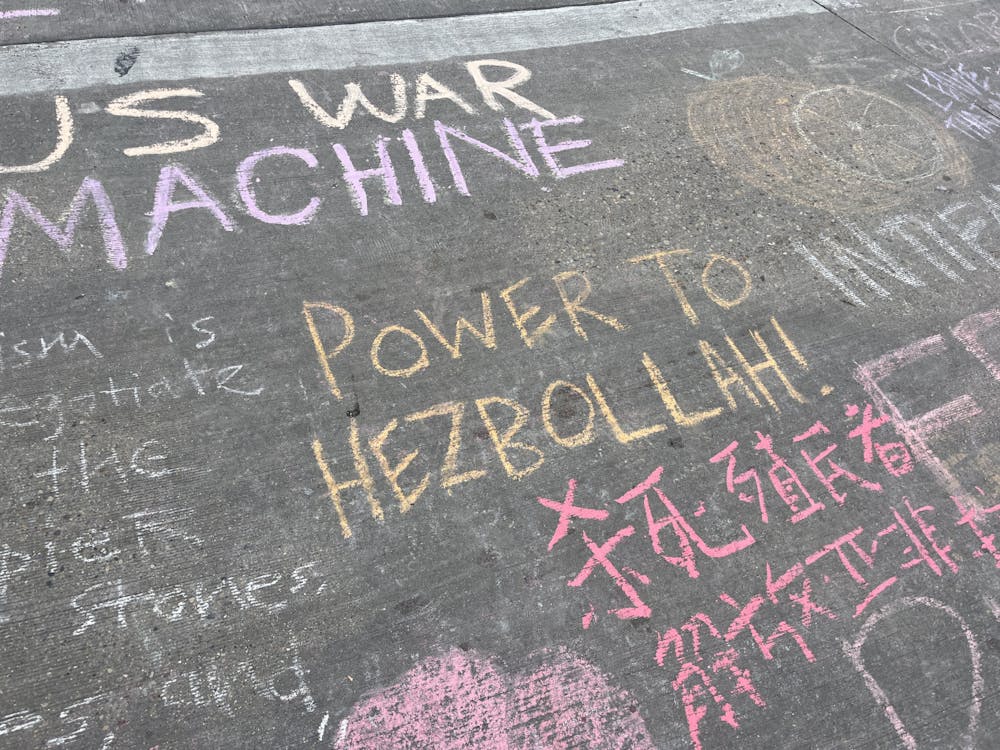

During the course of the encampment, antisemitic chalk messages endorsing Hezbollah, the Houthis and the military wing of Hamas were found at the Dane County Farmers Market. The chalkings, not associated with the encampment, were among the key concerns of each of the representatives.

For Subeck, the antisemitic chalkings took on a more personal note. As a Jewish woman, she said she feels worried for the safety of Jewish students on campus and the impact such remarks might have on them.

“I can only imagine being a student on a college campus, in some cases on your own for the first time in your life, and this is what you’re encountering,” Subeck said.

Murphy called the chalkings “hate speech” and said the administration’s actions were overly lenient.

“If the Klu Klux Klan was on a campus promoting antisemitism, I mean, their hair would be on fire with the administration… [but] you have a group of people espousing the exact same types of things with no repercussions,'' Murphy said.

Hong, who discovered Islamaphobic messages near Langdon Street during the encampment, said the hate speech near the encampment didn’t define the overall experience or beliefs of anyone there.

She also spoke with members of the community and a variety of students, many of whom felt unsafe from the encampment while others told her it was “the safest they felt in a very long time on campus.”

When the Cardinal told Murphy some Jewish students felt safer within the encampment, Murphy said there are “Jew haters within the Jewish community,” which did not surprise him. “They're putting liberal politics over their ethnicity and their religion,” he noted.

Hong and Subeck propose student affinity spaces

Hong said in August she hopes to see a number of new resources to aid students and staff in organizing for their voices to be heard and in giving affinity spaces where they can feel comfortable exchanging opinions.

“I think we have to prioritize staff support in addition to a physical space in which students know that they're going to be in an affinity space, where you don't have to constantly prove that what you're going through is painful,” Hong said.

Subeck echoed Hong’s endorsement of expanded programs for students to have spaces where they can debate their viewpoints in a safe and regulated environment.

For Hong, the proposed projects are a pivotal turning point in what she sees as a lack of support and community spaces for those who were oppressed or struggling to find a circle during Israel’s ongoing war on Gaza. Hong said she hopes to use her platform to advocate for more spaces in which conversations can be had in a safe environment.

“Jewish safety is intertwined with Palestinian safety. Asian safety is intertwined with Black safety. I think we're moving towards understanding that our collective safety requires us to be in solidarity with one another,” Hong said.