I owe you something, and you owe me something, too. I have no idea who you are, and you’ve probably never met me before — but that’s the point.

Think about it: when you walk into a campus building, and you know a stranger is just a few seconds behind you, do you stay and hold the door? Does it change if you’re having a bad day? More importantly, do you owe that act of kindness to the person behind you?

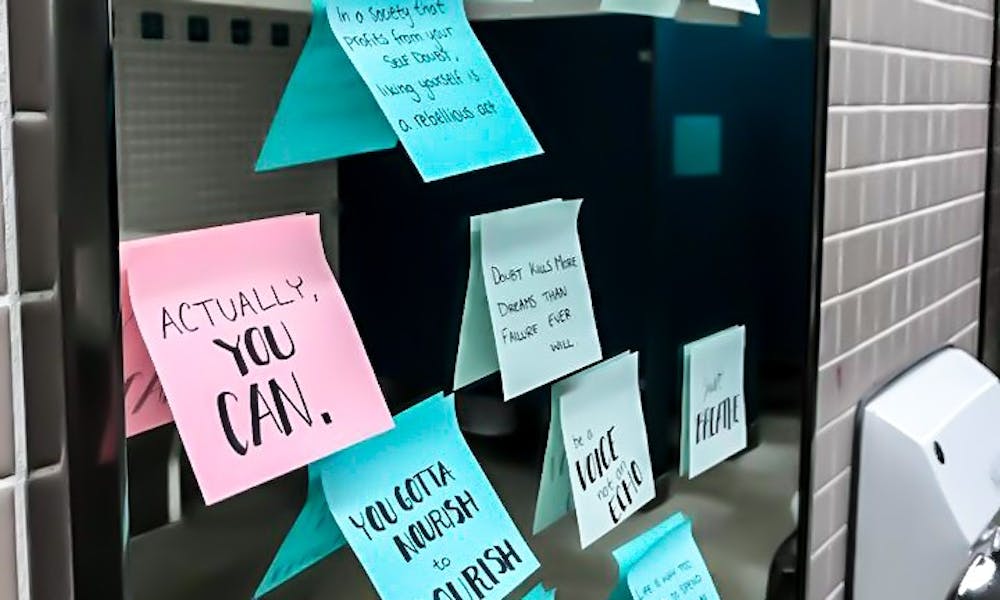

Today, the idea that “you don’t owe anyone, anything” thrives in primarily digital self-care spaces. For the most part, it comes from a good place. When we’ve had a long day, or we just aren’t feeling our best, it’s important to focus on treating ourselves with kindness. Maybe, when we’re feeling overwhelmed, or lost in our own thoughts, it’s okay that we let the door close on a stranger.

But the first time I read the words “you don’t owe anyone, anything,” while scrolling through self-care content on TikTok, I couldn't stop thinking about it for a week. In the days that followed, I started to see this rhetoric in practice everywhere I looked.

Modern interpretations of self-care mantras like this have become social cheat codes for our own bad behavior. In pursuit of self-care, we have convinced ourselves that lapses in kindness are a means of putting the self first.

From excuses made about doors closed in strangers' faces to glares exchanged for smiles on the street, it’s become clear that in an attempt to care for ourselves, we’ve lost sight of our duty to care for others.

But where did the idea that we “don’t owe anyone, anything” come from?

Looking back to 1966, we find the first notable use of the phrase in Harry Browne’s “A Gift for My Daughter,” in which he claims the best Christmas gift he could give was the “simple truth” that “no one owes you anything.” However, Browne, a two-time Libertarian Party presidential nominee, wasn’t speaking from a place of personal leniency and self-care, but instead arguing in favor of hyper-individualism and self-reliance.

So how did the rhetoric of a libertarian politician become a mantra for modern self-care?

Over time, the self-care movement has become rather unrecognizable. The origins of the self-care movement were inherently political, getting its start in the 1960s as a form of radical self-preservation adopted by Black civil rights activists. Foundational writers and thinkers like Audrey Lorde and bell hooks focused on self-care as a means of survival and a method of community care.

Now, instead of serving as a means of political resistance, the landscape of modern self-care has become dominated by consumerism and the same hyper-individualism Browne spoke about. From bubble baths to face masks peddled by influencers, quick-fix self-care solutions have become a perpetual carrot on a stick designed to keep us, above all, in constant pursuit of our own wellness.

But it’s important to ask ourselves — is this really self-care?

In the words of bell hooks, “whether we learn how to love ourselves and others will depend on the presence of a loving environment. Self love cannot flourish in isolation.”

We all owe each other something: a conscious effort to uphold the right to exist in a community of care. While it might be tempting to focus on ourselves, and ourselves alone, we can’t ignore that our own wellbeing often relies on those around us.

Next time you get the chance, you owe it to yourself, and to the stranger behind you, just hold the door.

Blake Martin is the opinions editor for The Daily Cardinal.