For college students, the effects of non-apparent disabilities — like depression, anxiety, ADHD, autism and other health related illnesses — transcend simply managing symptoms.

Not only are their symptoms invisible, but they face extra — and often overlooked — social and academic challenges that interfere with the “traditional” college experience.

Students with non-apparent disabilities are subject to social struggles even before arriving on campus. Morgan Stieber, a freshman who experiences chronic headaches and migraines, recounts her difficulties finding a roommate.

“It took me such a long time to find someone who was willing to work with me in the way that I needed to minimize the triggers in our room,” Stieber said. “Even now, it's hard to bring up the subject because I worry that it'll be too much, and it'll put unnecessary strain on our relationship.”

Outside of roommate relationships, students with non-apparent disabilities are burdened with consistently explaining why they cannot participate in activities that many prescribe as things “all Badgers do” — whether that be attending football games or drinking at bars.

“Something I've chosen to do is not drink alcohol, and a lot of that is due to having ADHD because it predisposes me to being more affected by alcohol,” said David Sauceda, a UW-Madison sophomore. “It definitely has an effect on how I interact with my peers.”

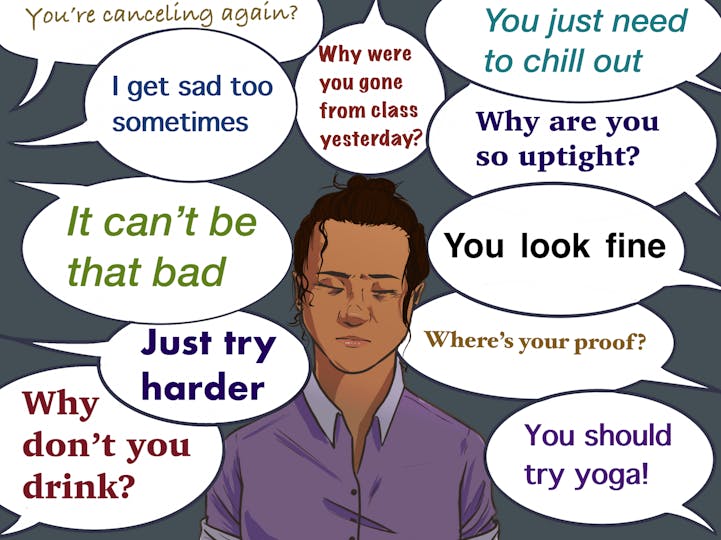

Peers, and even long-term friends of students with disabilities, seemingly expect an explanation for everything they view as “deviating from the norm.”

"Sometimes I need to use a handicap parking pass to get around campus, and when people find out they ask, 'Why do you have a pass? You look fine,’" said Kate*, a graduate student with POTS, a heart condition that is often characterized by fainting.

Jordan Hart, a sophomore who has major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, added, “When I had to go back to class after testing in a separate room, and I had to explain to my friends where I was during the test. I felt embarrassed,” Hart said.

Hart, Sauceda and many other students are subject to social encounters that can feel more like interrogations than friendships: they face fatigue, exhaustion and isolation not only from their symptoms, but from society's expectation that people need to explain their accommodations if they do not have a physical disability.

“A lot of campus culture, and society in general, doesn’t really empathize with what survivors go through and deal with. [Professors and other students] feel the need to get justification … to feel sympathy,” said Saja Abu Hakmeh, the chair of PAVE and someone who works with students who struggle with depression, anxiety and PTSD.

Academically, students with non-apparent disabilities often face non-apparent challenges that peers, professors and the university fail to recognize. Mandatory attendance and participation policies, for example, can have a detrimental effect on students’ grades.

Flare-ups in disabilities are part of what makes it a challenge for students with non-apparent disabilities to remain present during lectures or class discussions, damaging their participation grades.

“I have an extreme sensitivity to fragrances, and some days I have no choice but to sit in lecture or discussion with someone who is wearing some sort of perfume … and I can’t focus in class,” Stieber said.

In Kate’s experience as a STEM major, strict attendance policies made making up labs a difficult task.

“Mandatory attendance policies were really hard for me as an undergrad,” Kate said.

Kate was frequently hospitalized in order to treat flare-ups as an undergraduate. Those visits happened to be during two exams for one of her physics courses — and since the physics department does not offer any make-up exams, she had to drop the class.

Clearly, students with non-apparent disabilities are being harmed by several rigid class and university policies.

Missed classes and reduced participation are often out of the control of students with disabilities, so mandatory attendance and participation policies disproportionately affect those scholars. Consequently, professors should be more flexible when designing their grading system.

While the university claims they are focused on mental health and are striving to provide accommodation for students with non-apparent disabilities, their efforts do not always include all students. McBurney can be a great resource, but students with a pending official diagnosis from a medical professional lack the support it is capable of providing.

Julia Wagner, a third-year transfer student who has autism, spoke about the need for all students to receive accommodations if they need them.

“I think it’s a pretty simple solution … what I think McBurney should do is start working with students, start helping them right away,” Wagner said.

In essence, while students work toward receiving an official diagnosis through UHS or another medical health provider, McBurney could offer students a trial run of receiving accommodations.

“They can still have students jump through the hoops that McBurney is required to have them do,” Wagner said. “But in the meantime [of receiving an official diagnosis] students shouldn’t lack the support they need.”

Furthermore, getting the official diagnosis required for an accommodation letter is not as straightforward as many assume — some students lack the insurance needed to get a diagnosis, while others have had traumatic experiences in therapy and are unable to return to a therapist to receive proper documentation of a mental health condition.

While McBurney can be accommodating of many students with non-apparent disabilities, there are several others who do not receive those benefits. Professors need to shift their focus from accommodation to inclusion. Classes should be designed through the lens of students with diagnosed and undiagnosed disabilities.

In addition to eliminating mandatory attendance and verbal participation policies, professors can include practices as simple as starting classes with brain warm-ups and providing Google Surveys for students to ask questions without having to draw attention to themselves during class.

Mandatory training for professors to learn more about how various disabilities — apparent or not — would result in these more inclusive classes and policies, which could begin to fill in for where accommodations fall short.

“[Mental illnesses] affect everyone differently, but professors should understand how students’ experiences can vary,” Abu Hakmeh said.

Even without specialized training, professors should be proactive in reaching out to students, as it can be difficult for some students with disabilities to ask for what they need.

Many of the aforementioned solutions were suggested by students with non-apparent disabilities. And while the university should be listening to those students when constructing policies, students with invisible disabilities should not be burdened by both their symptoms and the construction of class policies.

“It can be hard to assess who needs accommodations,” Hart explained., “A welcoming, forward-thinking approach [by professors] can help.”

It is through a deeper understanding, and by simply having empathy, that our professors can make classrooms more accessible and inclusive for all students. This understanding can begin through one-on-one conversations with the very students this university may claim to — but, as spoken to above, still largely do not — include.

“If people have questions, I want them to ask me. I don’t want them to make assumptions,” Kate said. “Having a general openness to help and be inclusive is huge.”

*An asterisk indicates that the student interviewed wishes to keep their identity private, and a pseudonym is used in place of their real name.