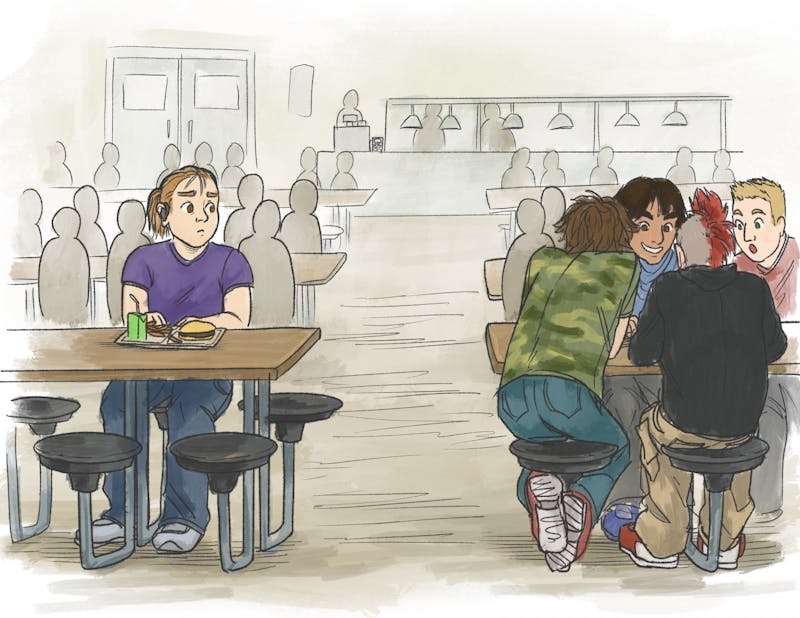

The implications of having a learning disability can extend beyond the classroom.

Image By: Max Homstad

The implications of having a learning disability can extend beyond the classroom.

Image By: Max HomstadThe chances you know someone with a learning disability are higher than you might think.

In the 2018-19 academic year, three percent of Wisconsin students — and 2.8 percent of Madison Metropolitan School District students — were identified as having a specific learning disability, according to the Wisconsin Information System for Education.

A specific learning disability is a disorder involving basic psychological processes — typically understanding or using language — that may manifest itself in an imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write or perform mathematical calculations.

But the implications of having a learning disability extend beyond the classroom as well.

Mentoring change

Eye to Eye is an organization run by and for individuals with learning and attention issues aimed at helping young students understand their learning and attention issues — and succeed with them.

The organization operates nationally, but its UW-Madison chapter, which began in 2014 with university students working with Wright Middle School students, is the largest in the country.

Clare Hartman is one of UW-Madison’s Eye to Eye Chapter Leaders and a fifth-year at the university. She was diagnosed with a learning disability, ADD, when she was a sophomore, but she always knew it was there.

“No one really knew my issues. Only I knew my issues,” Hartman said. “I always knew I had a learning disability, I just was unable to talk to my parents about it. And I had good grades, which was part of the issue. It was like 'Oh, you're doing pretty well, there's no way.'”

Now, through Eye to Eye, Hartman and other UW-Madison students with learning disabilities visit Wright Middle School once a week after school throughout the academic year to work with students with disabilities and even some yet to be diagnosed.

Hartman stated that art room — their time with the students — provides a creative space to look at short- and long-term goals.

"One kid was saying how they want to get better at Fortnight, but then we were like 'Why don't we focus on a long-term goal?' And he goes, 'I want to be a finance banker!'” Hartman explained. “So he made a briefcase. But for the short-term goal, he made a video game controller."

Eye to Eye changes students with LDs mindsets, according to Mary Birmingham, the school psychologist at Wright Middle School.

“The whole motto is if I can do it, you can too,” Birmingham said. “We had one young man who was struggling to read in eighth grade and his mentor, who was a graduate student in engineering, looked at him and said, 'Hey dude, I didn't learn to read until eighth grade either! But look at me now.'”

Eye to Eye changes students with LDs mindsets, according to Mary Birmingham.

Barriers of invisible disabilities

Eye to Eye’s vision is for students to live in a world in which people with Learning Disabilities and ADHD are fully accepted, valued and respected — not just by society, but also by themselves.

Hartman furthered that being a part of Eye to Eye and finding people with similar experiences to herself has been, well, “eye-opening.”

“They understand where I'm coming from as opposed to [others] who don't understand what you've been through,” Hartman said. “It's hard because I went to a doctor and she was like, ‘Your grades are too good,’ and I said, ‘No, I don't feel like I'm doing well.’ And that's the thing with something that's so invisible: you feel alienated.”

Debra Heiss, interim consultant for students with specific learning disabilities with the Department of Public Instruction, helps provide guidance to school districts across the state.

She stated that though there are great benefits to being diagnosed with an SLD, like additional services, often teachers and family members will expect less of those students.

“I think there’s a real push to identify students as having a disability and there isn't always a great deal of thought given to the disadvantages of that,” Heiss said. “One of the most significant barriers is that whenever we identify an individual as having a disability or specific learning disability, we change what individuals expect of that person.”

Birmingham has been the school psychologist at Wright for 18 years and helps provide students understanding of both the social-emotional and academic impacts of LDs.

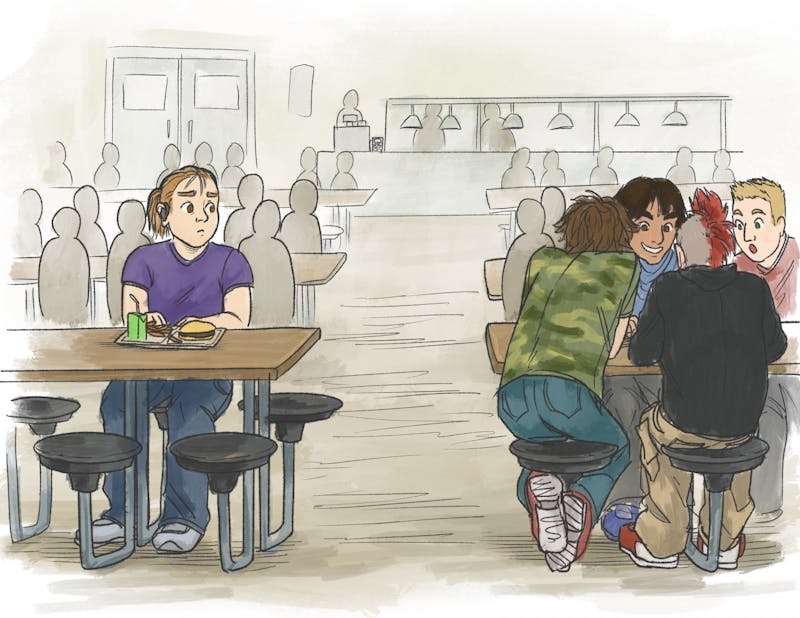

“Students with learning disabilities often don't want additional support in the classroom because they don't want to seem different from other students,” Birmingham said. “A lot of them have binary thinking of that there are smart kids and dumb kids and I'm one of the dumb kids because I learn differently.”

To combat this, Birmingham explained Wright Middle School’s morning routine: students start their day in an advisory classroom, working on building community, the language of respect and examining how to support one another.

Birmingham also meets with students individually and stresses the importance of openness surrounding LDs. And not just giving knowledge, but also talking about how students feel.

She explained how even well-intentioned family, teachers and more can foster a sense of “learned helplessness,” meaning people do things for students with LDs rather than helping them do it themselves.

“Every single student with a learning disability has a different need, so we have to be individualistic in what we do,” Birmingham said. “It's really important that support looks empowering and facilitates a sense of ‘I can’ versus ‘You can't.’”

Through Eye to Eye, Clare Hartman, above, and other UW-Madison students with learning disabilities visit Wright Middle School to work with students with disabilities.

The local impact of federal actions

On top of helping schools appropriately identify students with SLDs in the fairest way possible, the DPI has also focused on social and emotional learning for all students. For kids with SLDs, that means providing intervention, high quality services and closely examining ‘all means all,’ according to Heiss.

Despite these efforts, states and local school districts remain focused on results and specific testing outcomes — the federal initiative Results Driven Accountability emphasizes the data behind the students.

Wisconsin has chosen literacy outcomes for this initiative, as it’s an area of challenge for many students with disabilities. Intended to help districts meet national and state testing requirements, the DPI states that RDA maximizes efficiency in implementing practices that improve outcomes for students.

Students diagnosed with specific learning disabilities represent 35 percent of all students receiving special education services, according to the Learning Disabilities Association of America. But those services have seen a sharp decline in funding over the past decade.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act is a federal law that ensures special education and related services in public schools.

Part of this is developing an Individualized Education Program, or IEP, which details exactly how the school plans to help a student improve and build skills. It is necessary in order to receive special education support.

However, the National Education Association reported that the cost of educating children with disabilities is twice as high as educating those without. At IDEA’s establishment, Congress determined the federal government would pay up to 40 percent of this excess cost, which Congress considers full funding — but it falls short.

Additional costs not covered by the government are shifted on to states and school districts, which has averaged almost $19.5 billion since 2009.

Birmingham, who has worked within MMSD for over 28 years, has seen first-hand the district’s struggle to support special education services.

“There are just not enough resources in public schools to meet the needs of all of our diverse learners,” she stated. “The amount of funding cuts that have happened to special ed, in the state and federal budgets — it's quite dramatic.”

The consequences can be seen in the classroom, with less special education assistance available and fewer material resources, like noise-canceling headphones.

And while Birmingham pushes for more funding and general education for special ed, some believe that if folx with disabilities were more visible and valued in society, there would be no need for specialized services at all.

Tonette S. Rocco’s proposed Critical Disability Theory highlights the problems those who have disabilities face and proposes that, rather than separating and isolating, we as a society should instead modify the environment to those with disabilities, in order to “de-disable” them.

For example, in higher education settings, students with disabilities must go to an office specifically serving disabled students to verify disability status and request accommodations. Even then, students are refused rights by instructors, accused of lying about their disability or ignored by classmates.

“Discrimination is invisible to the perpetrator yet painfully felt by the victim,” Rocco writes. “Disabled people’s voices are not heard because they are not asked or are ignored.”

Special education support systems, like Eye to Eye and IEPs, give students with LDs more agency, and therefore more of a voice.

But, as Rocco proposes, perhaps it is time to examine whether that is enough.