Madison is segregated not only by race and income, but by levels of environmental risk.

Madison is segregated not only by race and income, but by levels of environmental risk.

Imagine being at risk of a chemical explosion next to your house or being more likely to get cancer because of the place you live. Your neighborhood is toxic, but it’s all you can afford.

For minorities and low-income individuals in Madison, this is more than likely a reality.

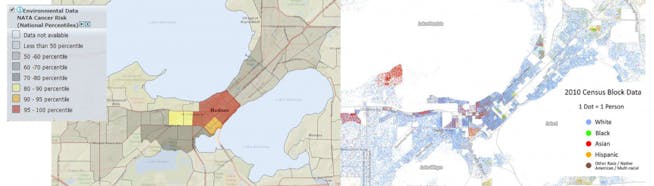

A 2016 report by the Center for Effective Government graded states on how many people of color and residents who are low-income that live within one mile of dangerous chemical facilities compared to white and high-income people. Wisconsin received an “F” grade — the only state besides Massachusetts to fail.

Early housing policies have had lasting effects on Madison’s environmental landscape, with people who are low-income and communities of color living closer to harmful facilities.

Children of color were found to be twice as likely to live near a hazardous chemical facility than white children. Many of the state’s high-risk facilities are located in Madison, Milwaukee and Fox River Valley.

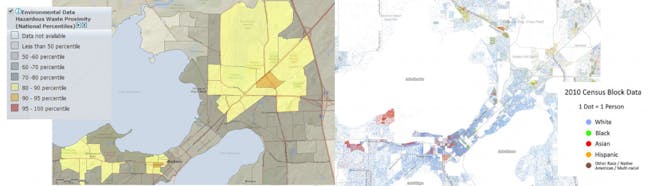

Over half of the populations in areas in the 80th-95th percentile for hazardous waste proximity fall below the poverty level, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s environmental justice screening and mapping tool EJSCREEN.

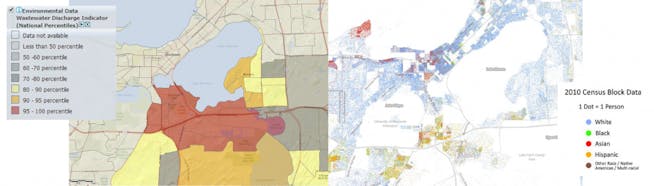

Low-income neighborhoods are also more likely to have contaminated water in their homes, particularly on Madison’s East Side.

Some of the contaminants found in city wells include per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS. These man-made chemicals are used in firefighting training, which takes place near Truax Field and Dane County Regional Airport.

In a well less than a mile from the Truax Airfield, groundwater was tested to have a PFAS level about 569 times higher than is safe for human health.

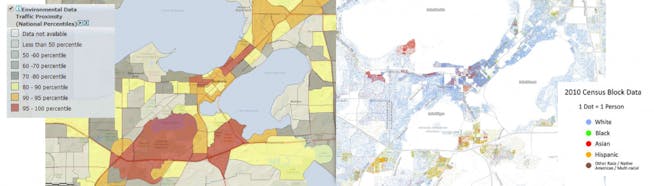

The contaminated water disproportionately affects low-income residents with historically underrepresented identities in the Truax neighborhood. The neighborhood is one of the most polluted and traffic congested areas in the city because it is adjacent to Highway 151 and Highway 51, according to Touyeng Xiong, a board member of the Midwest Environmental Justice Organization.

This neighborhood is just one example of environmental inequalities that parallel the demographic outline of the city. Many areas with the most concentrated minority populations on the Racial Dot Map also have the highest percentiles on the EJSCREEN map.

“The city buys the cheapest land they can get, which is next to areas contaminated with chemicals or pollution,” Xiong said. “Low-income minorities can’t do anything because they just want affordable housing. They are not responsible for causing these problems but are the people most at risk.”

Many areas with a large population of low-income residents also have the highest percentiles in traffic proximity, wastewater indicators and cancer risk.

“Some environmental variables generally do correlate — not just in Madison but in many other cities as well — with proximity to traffic corridors, which correlate with things like ozone and vehicular air pollution exposure and with age of housing stock which correlate with things like lead paint and other indoor pollution hazards,” said William Cronon, the director of the UW-Madison Center for Culture, History, and Environment.

This pattern emerges in many cities because rent is often cheaper in hazardous environments and more affordable for people with lower incomes, according to Cronon.

“[Environmental hazards] have significant impacts on real estate values, which in turn correlate with rents — which is an important reason that people with lower incomes often find themselves forced to live in places where they're at risk for problematic environmental exposures,” Cronon said.

The inequality in Madison’s housing structure goes back to city zoning policies and private developer contracts crafted in the early 20th century. Municipal governments used the same rules as developers to divide up cities into residential, commercial and industrial areas.

These zoning rules, according to UW-Madison history assistant professor Paige Glotzer, created industrial dumping grounds for hazardous materials such as factories and waste disposals, predominantly in poorer and minority neighborhoods.

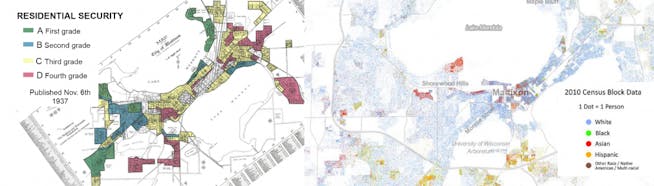

These local policies became federal laws to provide lending support for people’s mortgages during the Great Depression era. Major cities including Madison were carved out and areas were given grades, determined by how risky it would be for the federal government to offer local residents assistance.

“The use of a property, the race of a person and kind of environmental conditions contributed to essentially whether areas and people living in areas were going to receive a mortgage bailout,” Glotzer said.

Residential areas with declining houses and hazardous industrial facilities created from zoning policies were redlined, which was a practice that segregated neighborhoods by their "residential security"—usually along lines of race and class — and denied services to lower ranking neighborhoods.

This also meant that those who are minorities and economically disadvantaged could not receive assistance to move to environmentally safer neighborhoods.

“Allocation of resources that began at the local level became national policy that really dictated growth and mobility of people at all levels,” Glotzer said.

The segregation of neighborhoods left a lasting influence, yet activists continue to fight for more equitable zoning policies.

“There’s no reason given technology today that a lot of Madison waste disposals all have to be concentrated in one area along Badger Road,” Glotzer said. “So why is it that old patterns of environmental hazards are still being practiced when technology may have moved beyond that?”

Many environmental justice groups, such as the Midwest Environmental Justice Organization, are fighting the city’s inequalities, but Rep. Shelia Stubbs, D-Madison, believes that minority voices need to be at the forefront.

“Little room is left for participation by lower-income individuals and people of color when environmental conversations and goals are dominated and determined by the white majority,” Stubbs said. “In the pursuit of a more just and inclusive environmental movement, the voices and concerns of marginalized social groups must be elevated and heard.”