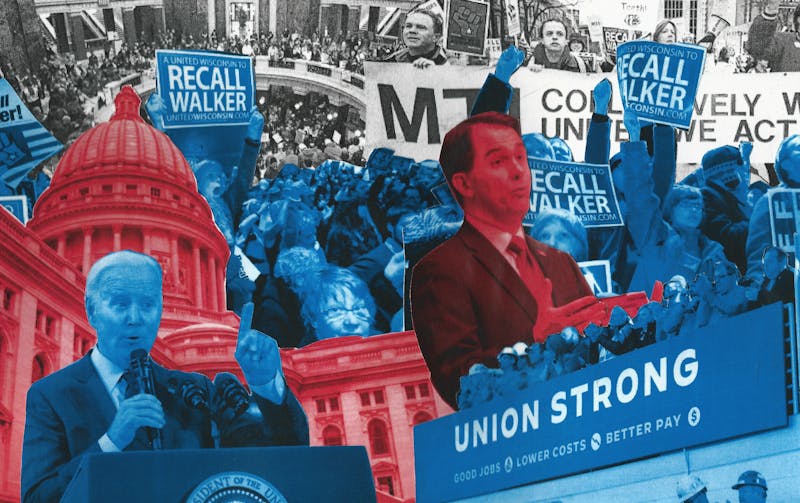

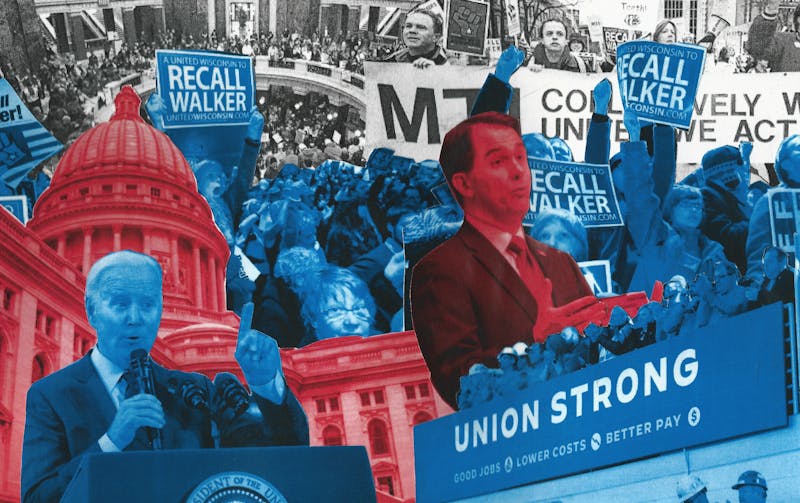

Wisconsin was one of the nation’s leading states in labor rights before a steady decline in union membership and Act 10 sank its standing. Could growing approval and presidential pandering put unions back in the spotlight before the 2024 elections?

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, union favorability is on the rise after years of decline. Recent Gallup polling found 71% of Americans approve of labor unions — the highest level since 1965.

But in 2022, only 187,000 Wisconsinites were union members — a 13% drop from 2021 and the lowest number recorded since at least 1989, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Additionally, with union membership at 7.1%, Wisconsin’s labor unions trail the national average by 3% and neighboring states Minnesota, Illinois and Michigan by at least 4% each.

Despite years of decline, Wisconsin used to be one of the most unionized states in the nation, according to the Center for American Progress.

Michael Childers, co-chair of the University of Wisconsin’s School for Workers, said policies like Act 10 and right-to-work laws made it harder for Wisconsin employees to unionize in the past decade. However, heightened public favorability and campaign moves from Democratic politicians, including President Joe Biden, could launch Wisconsin’s unions back into the spotlight ahead of Wisconsin’s 2024 elections.

“The relationships that we [Democrats] have with unions are instrumental in what we both aim to achieve, which is economic security and solidarity with all workers,” said Rep. Kristina Shelton, D-Green Bay.

Two members of the Laborers’ International Union of North America (LIUNA) look on as President Joe Biden delivers a speech to a crowd of hundreds at a labor training center in DeForest, Wisconsin on Feb. 8, 2023.

Rise and fall of Wisconsin unions

For many decades, the Midwest was the region with some of the highest rates of union membership. In 1964, the highest concentration of U.S. union workers was in the Midwest, according to data from NPR. This included 34% of Wisconsin workers who were union members, a total nearly five times greater than in 2022.

What stood Wisconsin apart from the rest of the nation was that its Legislature passed labor laws ensuring workers' rights much earlier than other states and refrained from passing restrictive laws, according to Childers.

While in the 1940s the Southeast and some Western states passed section 14 of the Taft-Hartley Act – or “right to work” laws – the industrialized Midwest initially held off, Childers said. Wisconsin would not pass a similar law until 2015.

“That was a change to labor law in Wisconsin, that's pretty recent that traditionally had never been an issue here,” stated Childers.

In 1959, Wisconsin was also the first state in the U.S. to authorize public sector workers to organize and bargain with their employers — a right previously only guaranteed to private workers under federal law — with the passing of the Municipal Employment Relations Act.

Union membership in Wisconsin slowly declined over the latter half of the 20th century and into the 2000s, following national data trends from NPR. By 2010, just 14.2% of workers in Wisconsin were part of a union, though the state’s unionization rate was still higher than the national average of 11.9%, according to Wisconsin Public Radio.

However, that trend would reverse after Republican Gov. Scott Walker signed off on legislation limiting collective bargaining rights for public employees a year later.

Prior to Act 10’s passage, an estimated 1.5 million people, including Wisconsin teachers, firefighters and other unionized public employees, descended on the State Capitol building for weeks of protest. Members of the UW-Madison Teaching Assistants’ Association and some other protestors occupied the Capitol, sleeping inside for days. Meanwhile, 14 Democratic state senators fled to Illinois to avoid voting on the bill.

Educators believed “a teacher’s working conditions are a student's learning conditions,” Childers explained.

But with support from the Republican-controlled Wisconsin Legislature, Walker passed Act 10 in March 2011, which Childers said greatly curtailed public sector workers’ ability to bargain with employers as a union.

Under Act 10, unions must garner 51% of support from all employees every year to remain active. Employees who don’t vote are essentially counted as “no” votes, Childers said.

“It actually requires 51% of the eligible voters — not of the votes cast, [but] of the amount of people that would be a part of the bargaining unit,” he explained. “By those rules, I don’t think we would have elected any president for the last 40 years.”

If the union does end up recertifying, they are only allowed to bargain their wages with employers, according to Childers.

“You’re going to go through a lot of work to basically talk about very little,” Childers said.

In order for Democrats to gain control in the Assembly and Senate to repeal “right to work” or Act 10, they need both the voting numbers and a major revision of Wisconsin’s voting district boundaries.

“Wisconsin has its own set of issues with the way the congressional maps have been drawn,” Childers said. “Unless that gets sorted out, I don’t see anything changing.”

As a pager at UW Health, Nathan Reid connects callers to doctors and answers emergency phones. Reid said working conditions for pagers declined after Republican Gov. Scott Walker signed Act 10 in 2011, limiting collective bargaining rights for Wisconsin's public employees.

UW Health employee recalls union decline after Act 10

Without the protections unions provided, pagers at UW Health have felt the conditions worsening at their place of work since Act 10’s passage.

Nathan Reid works as a pager and messenger at UW Health, a 24-hour department where he connects callers to doctors and answers emergency phones. When Reid started, pagers were a part of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), the same union that represented UW Health Nurses. Reid felt he had the “full weight” of organized labor behind him.

“It wouldn't just be you, or wouldn't just be a bunch of individuals, you had the SEIU,” Reid said. “That's one of the biggest health care unions in the country.”

But when the union was phased out following Act 10 — just six months into Reid’s tenure — he noticed a decline in benefits.

“One of the very first things that changed was every employee had to get a very small percentage, like [a] 10 to 11% raise to compensate for the fact that with the unions going away,” Reid said. “Everyone's health benefits — and essentially everything that comes out of their paycheck every two weeks — was all going to go up.”

Without SEIU, UW-Health was able to do whatever they wanted, Reid said. He and other employees felt they were “treated as items rather than people,” he added.

“It's hard to explain to people who have only been hired in the last year or two, what it was like,” Reid said. “There seemed to be a lot more camaraderie. There seemed to be a lot more enjoyment in what people did with their job from day to day because they had those extra assets.”

With health workers forced to spread themselves thin with little support, compensation or extra incentives during the COVID-19 pandemic, Reid said he and others began to feel overwhelmed and overworked. Almost half of the long-term pagers quit within the pandemic’s first year, according to Reid.

“Those were all employees who had been there through the unions, and they lost a lot of their benefits because the unions went away,” he added. “COVID just made their jobs unbearable.”

Although working conditions worsened during the pandemic, Reid said it created an environment where employers were forced to create better working conditions for their employees or face mass quitting.

“COVID had the effect of, in a strange way, almost creating some of what a union is trying to achieve,” he said. “Things got so bad because of COVID, that it forced UW Health to not be able to ignore all the grievances people were having.”

While COVID created conditions where employers like UW Health had to improve working conditions, Nate was left contemplating all he and his fellow co-workers went through to see these changes.

“Work got so grim and hard, and it affected so many people in such a negative way, that it almost makes you wonder, ‘Was it worth the cost of it?’” Reid added. “But at least it got the attention of UW Health as a whole.”

University of Wisconsin-Madison graduate student union members of the Teaching Assistants' Association occupied the Wisconsin State Capitol in 2011 to protest of Act 10, a proposal supported by Gov. Scott Walker and Republican lawmakers that would limit collective bargaining rights for public employees.

COVID brings changing perspectives on unionization

Although COVID brought hardship for nurses and other essential workers, the pandemic helped change people’s views on their relationship with work and wide disparities in benefits, Childers said.

“A lot of frontline workers who were being told, ‘You’re essential’ — they’re believing it,” Childers said. “They’re like, ‘Well if we’re essential, why should we have to work two jobs to be able to make our bills or be able to have a decent life?’”

Five Starbucks locations in Wisconsin have made successful efforts at unionizing in 2022 after protests, strikes and petitions to the National Labor Relations Board. In July 2022, the Starbucks at Madison’s Capitol Square voted overwhelmingly to unionize.

“[Wisconsin Starbucks growing unionization] shows that even, despite whatever clause we still have in our labor law, workers are going to try to come together when they feel like they are not being heard or that things are unfair,” Childers explained.

Additionally, UW Health nurses — who faced severe staffing and health benefit cuts with additional hours of work even before COVID exacerbated their working conditions — are currently trying to reinstate their union.

In early September, the nurses planned a three-day strike but instead negotiated a compromise plan where they would begin talks with the Wisconsin Employment Relations Commission on whether UW Health can lawfully recognize a nurses union. Under the compromise, nurses agreed not to organize another strike so long as UW Health negotiated in good faith.

While some union leaders took the agreement as a sign of hope, Reid remains cautious.

“To be perfectly honest, a lot of us [pagers] were wishing the strike had actually happened… those negotiations could take years,” he said. “It was a good way to really stop some bad publicity for UW Health.”

Whether the talks lean in favor of the nurses creating a union again or not, as Childers described, very little in terms of labor union law can change substantially until political demographics in the Legislature change.

“There’s no unity of purpose within our government [regarding] potentially reversing things like right-to-work or Act 10. I don’t see that on the horizon here in Wisconsin,” Childers said. “You’d have to have a major change in the Legislature for that to happen.”

President Joe Biden addresses hundreds of Laborers’ International Union of North America (LIUNA) workers gathered at a labor training center in DeForest on Feb. 8, 2023. During his speech, Biden shared his “blue-collar blueprint” to rebuild U.S. infrastructure with union jobs and promised to repair a “hollowed out” middle class.

Political appetite for unions

In a broader scope, state and federal lawmakers — including President Biden — are looking to capitalize on union frustrations and rising public support for organized labor in upcoming elections.

During his presidential campaign in 2020, Biden vowed to be “the most pro-union president you’ve ever seen.” As president, Biden passed two large bills — the Inflation Reduction Act, and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act — which the White House said incentivized employers to emphasize workers' rights and support unions.

“There’s a lot in those two large bills that were passed that [does] favor companies using union workers, which will increase demand for those workers which provides more family-supporting jobs,” Childers said.

Additionally, during a campaign stop near Madison following his 2023 State of the Union address, Biden promised a “blue-collar blueprint” to rebuild U.S. infrastructure with union jobs.

“Wall Street did not build this country,” Biden said in February. “The middle class built the country, and unions built the middle class.”

Recent train derailments across the country following Biden’s turn to Congress to stop a rail worker strike from occurring late last year left some voters questioning his commitment to the cause.

Still, Rep. Shelton said Democrats remain committed to engaging union voters ahead of the 2024 elections.

“When you bring folks together on economic security, you can and should talk about union power — but you also have to talk about things like clean water, good housing, childcare, strong public schools, criminal justice reform,” Sheldon said. “It creates an umbrella for which people can understand how the common cause of economic security really relates to all the other things.”