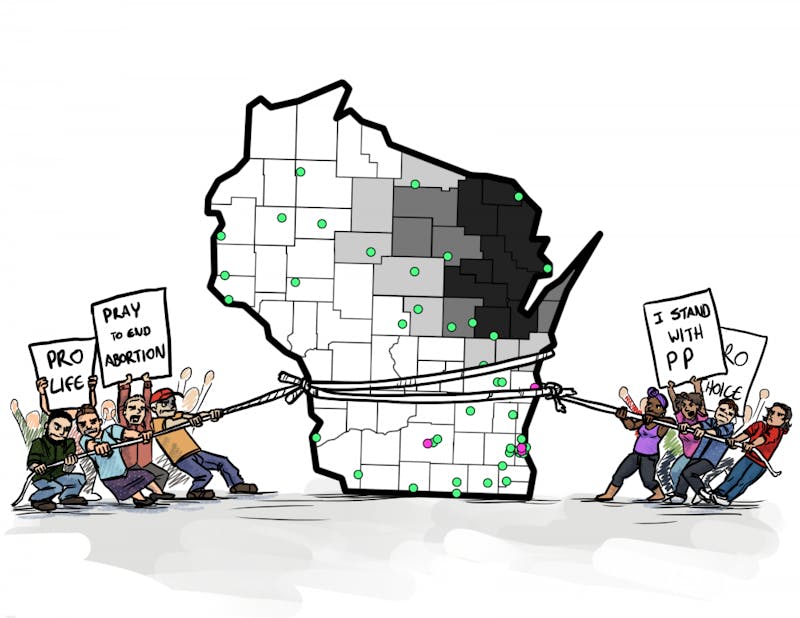

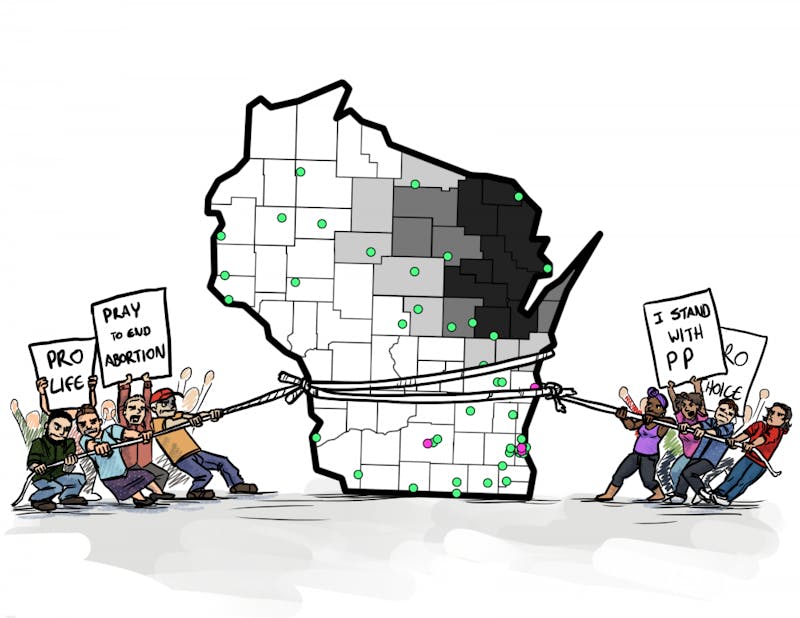

The expanding influence of health care institutions funded by religious groups in Wisconsin contributes to the changing landscape of women’s reproductive care and policy.

Image By: Tommy Valtin-Erwin and Max Homstad

The expanding influence of health care institutions funded by religious groups in Wisconsin contributes to the changing landscape of women’s reproductive care and policy.

Image By: Tommy Valtin-Erwin and Max HomstadGuided by economic incentives to promote a pro-life agenda, legislation has strained accessibility to abortion and other reproductive services across the state.

While the popular opinion that abortion should be legal to at least some extent remains intact — with 63 percent of Wisconsinites in favor, according to a recent Marquette poll — the growing power of life-affirming organizations fuels discussion about whether this topic is a public health or political issue.

About 40 percent of births in Wisconsin, a percent as high as any other state, take place in a religiously-affiliated institutions, according to UW-Madison Gender and Women’s Studies Professor Jenny Higgins. Wisconsin is also the only state in the country where African-American people are more likely to give birth in a religious hospital than a secular facility.

While there are many different religions associated with health care systems, the rise in Catholic and Christian institutions, in particular, is significant. What is notable about these clinics, hospitals and health centers is how their ideology limits the services offered to patients.

“Religiously affiliated health care centers do many types of health care well, however they do many aspects of reproductive health care poorly or not at all,” Higgins said. “This does not only refer to abortion, but also to things like tubal ligations, being able to get postpartum contraception, miscarriage management … and other aspects of reproductive health care.”

Higgins believes many Wisconsinites who want reproductive health care help are not receiving necessary support from public institutions.

The National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws — NARAL Pro-Choice America — found data supporting this lack of access, revealing that 67 percent of people in Wisconsin live in counties with no abortion clinic.

Growing distance from clinics challenges more than abortion accessibility

Although located in high population centers, only three cities in the state have health centers offering abortion services: Milwaukee, Madison and Sheboygan. Three out of four total locations are Planned Parenthoods.

These clinics have strict regulations about what days of the week abortions are permitted, the type of procedure allowed, the necessary protocol for a pregnant person to be approved for the procedure and more. Wisconsin law also requires doctors to show those considering an abortion a sonogram, as well as describe the fetus to them.

“In Wisconsin, anyone seeking an abortion needs to make two trips separated by 24 hours,” Mel Barnes, the legal and policy director at Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin, said. “That is not for any medical reason, it is solely because of state law that we require that. Women who are seeking a medical abortion have to see the same doctor on both of those visits. They have to arrange transportation, maybe getting off work, maybe child care and all of that stuff twice.”

However, abortion is not the only service Planned Parenthood offers, and due to an extraction of federal funding under former Gov. Scott Walker’s first budget, many locations were forced to close.

Planned Parenthood provides primary care for many patients, 10 percent of whom are men, Barnes explained while discussing the lack of general health care providers in the state.

“We do certainly always try to go to population centers and go where the need is. We are a critical part of the safety net in terms of trying to fill the gaps that exist,” Barnes said. “In 2011 we were forced to close five health centers in rural communities due to a loss of state funding, and we know that in those communities, no other providers have stepped in to take our place.”

A 2017 report from the Health Management Associates found nearly half of the counties that Planned Parenthood serves have no alternative health care provider for family planning services.

Data from the Wisconsin Policy Analysis Lab showed how these closures exacerbated the distance of the closest abortion-providing facility for Wisconsinites.

In 2010, the proportion of counties within a 30 mile radius of an abortion clinic was 24 percent. By 2017, the number decreased to 13 percent. Accordingly, the proportion of counties between 90 to 120 miles increased from 18 percent to 29 percent for the respective years.

The complicated rise of crisis pregnancy centers

While the number of pro-choice clinics has decreased, crisis pregnancy centers, like Pregnancy Helpline in Madison, have increased by 200 percent over the past four years, according to their Executive Director Stephanie Ehle.

Pregnancy Helpline, located just off UW-Madison’s campus, is a care facility offering services like maternity clothes, diapers and information for pregnant people. The organization is funded by churches, private donors and pro-life organizations.

“We try to stress that although we are a life-affirming organization, we are not a political organization or a religious organization we are really just trying to help those in need that chose to parent,” Ehle said.

Although most of the material goods Pregnancy Helpline offers cater to post-birth needs, they belong to an international organization and directory of many other crisis pregnancy centers attempting to provide before-birth medical services without having properly regulated licenses or credentials.

This means if a person called Pregnancy Helpline seeking medical attention, they would get referred to a local affiliate organization who influences those experiencing an unexpected or unwanted pregnancy to carry it to term regardless of circumstance.

Although they are advertised as health centers, their facilities are run by trained volunteers, not doctors, who offer blood tests, ultrasounds and support, rather than sexually transmitted infection testing, condoms or birth control options, like Planned Parenthood would.

Many centers have 24/7 emergency call lines for all pregnancy needs, often promoting this hotline for people considering an abortion, or wanting to hear about options. However, none of the centers provide abortions or will give information about where to get one, even if getting one would be in the person’s best interest.

Doctors and researchers Amy Bryant and Jonas Swartz wrote about this breach of choice in “Why Crisis Pregnancy Centers Are Legal but Unethical” in the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics.

“As nonprofit organizations, crisis pregnancy centers have the right to exist,” Bryant and Swartz wrote. “However, as we have seen, they also employ dubious communication strategies — withholding information about abortion referral, not being transparent about clinically and ethically relevant details, or using inflammatory language to scare women and dissuade them from having abortions.”

However, the article also mentioned the value centers like Pregnancy Helpline can have as a resource for those who do choose to continue to their pregnancy. Despite their initial intentions, these centers support clients by providing them with financial incentives.

In this way, Ehle said those centers are filling the gaps.

The lack of structural support from the state allows these centers to benefit those in need with resources, while simultaneously promoting their interests and biases about a person’s right to their body.

Higgins blames the weak social safety net neglected by the state government more than the crisis pregnancy centers themselves.

“Even though I think it's easy to get frustrated and angry because of the way in which they market themselves or the falsehoods that they convey to people about abortion, in terms of how many people they are actually deterring from getting abortions is few,” Higgins claimed. “Most crisis pregnancy center clients are people who are needing help and financial support during pregnancy and birth because they are not getting what they need from the state.”

Where Wisconsin abortion policy lands and why

Under current legislation, including the Medical Termination of Pregnancy Act, pregnancies can be terminated up to 20 weeks if the person is able to access care and complete required protocol.

However, Wisconsin is also one of nine states retaining their unenforced abortion bans from before U.S. Supreme Court Case Roe v. Wade — which ruled that banning abortions was unconstitutional — according to the Guttmacher Institute.

This makes Wisconsin a trigger state.

As a trigger state, if the U.S. Supreme Court were to roll back Roe v. Wade, all abortions in Wisconsin would immediately become illegal, including rape-induced pregnancies, unless they are performed to save the mother’s life under state statute 904.04. This statute also criminalizes physicians who perform abortions with felony charges.

Yet this statute does not reflect the Democratic desires of the majority of Wisconsinites.

In fact, 63 percent of respondents were in favor of abortion in all or most cases, compared to 29 percent who oppose it, according to a 2018 Marquette Law School poll.

While public opinion shows constituents support a pregnant person’s right to choose, the legislature remains split on the topic, pushing forward both pro- and anti-abortion policies.

Sen. André Jacque, R-DePere, whose photo is displayed as an endorsed 2018 candidate for Pro Life WI, spoke out about his interest in presenting new legislation to eliminate all abortion and Planned Parenthoods.

“It is also clear that UW-Madison is currently in flagrant violation of state statute 20.927 by paying state employees on state time and with state benefits and malpractice insurance to perform abortions under their arrangement at Planned Parenthood’s Madison abortion facility,” Sen. Jacque said. “There will be continued efforts to bring the UW out of willful noncompliance.”

The statute Jacque is referring to controls how the funding for certain insitutitions can be used. This includes UW-Madison professors who want to research certain aspects of reproductive health, forcing them to find private grants rather than employing their salary.

Higgins, who must check with legal counsel before conducting public health research, claimed this is an interruption that stymies her research.

“I do think that misogyny runs deep, sexism runs deep and I think that women’s reproduction has always been used as a way of exasperating gender inequality in our society,” Higgins said. “Cisgender men are the ones who are typically making that decision, and cisgender women tend to be the ones having the negative repercussions. That is something that makes me very uncomfortable in terms of gender justice or a gender equity lens.”

Pro-choice Rep. Melissa Sargent, D-Madison, said the reason women take the back seat in regard to reproductive options and health care funding is because there are so few women in charge of drafting and passing policy.

“If we had more women in our legislature, I tend to think that we would have more people who are prioritizing how we take care of our women and girls because they know first hand what it is like, and unfortunately the deck is stacked against us,” Rep. Sargent said.

But the disparities do not end there.

Sargent believes the disconnect between moderate and liberal Wisconsinite views on abortion compared to many conservative legislators is swayed by the powerful economic backing of life-affirming organizations.

“There's a lot of money behind the pro-life policies and those folks get on the front lines and support people when they are running for office and help them win their races. Then when they get in the Capitol building, they are reminded of how they got there, and it has an influence on policies that are put forward,” said Rep. Sargent said. “So, what we see in the legislature are actually people who are a bit more extreme than the ordinary people in our communities, and that creates the disconnect.”

During the 2018 midterm election, there were 37 Wisconsin candidates endorsed by the Pro Life Wisconsin Victory Fund political action committee who are considered 100 percent pro-life. Only six of these legislators were women.

As the split government looks to vote on the upcoming biennial budget proposal by Gov. Tony Evers, pending topics surrounding general health care funding and the lawsuit against the Affordable Care Act will be debated.

It is unclear how this will spark conversation or new legislation regarding Wisconsin’s stance on reproductive rights. However, due to the deeply rooted moral conflicts of this issue, it is likely that compromise is not nearby.

“I think if we could get to a place of [doing] everything we can to support folks in preventing pregnancies they don't want to have, having healthy pregnancies when they do want to and getting access to termination as well as birth services,” Higgins said. “… That is a crucial part of the fabric of public health.”