From the Vietnam War to pro-Palestine encampments, art as a form of protest and political expression has long been central to UW-Madison’s history.

In June of 1991, two members of LGBTQ+ rights organization Act Up! Madison put on diapers, bibs and frilly bonnets. They were protesting the denial of day care services to an HIV-positive mother in Madison, and though their method was uncommon, it garnered attention through art.

Madison is known for its extensive history of protest. But art and different forms of self-expression have been central to both social life and protest at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Many look back on protests during the Civil Rights and anti-war movement in the 1960s and 1970s and characterize them as just chants, marches or the occasional sit-in. But there was also creation — from graffiti, music, paintings, performances, poems and more, artivism has become central to UW-Madison.

As the Elvehjem building was constructed in 1966, soon to become the Chazen Museum of Art, a plywood fence around it became filled with political graffiti and street art.

Messages such as “Where is Lee Harvey Oswald now that we really need him?” were commonplace on the fence, alongside “Lock up McNamara, throw away Ky,” a reference to the secretary of defense and South Vietnamese prime minister. At its inception, the Chazen had already hosted UW-Madison’s protest art.

“Art has been used as a political device, protest or otherwise, for propaganda or for conveying an agenda of some sort,” Katherine Alcauskas, the chief curator of the Chazen, told The Daily Cardinal. “In fine art and in poster production, there's a lot of ways that images can tell very meaningful stories.”

Artwork, whether intended to be political or not, is often adopted by a political cause, she continued.

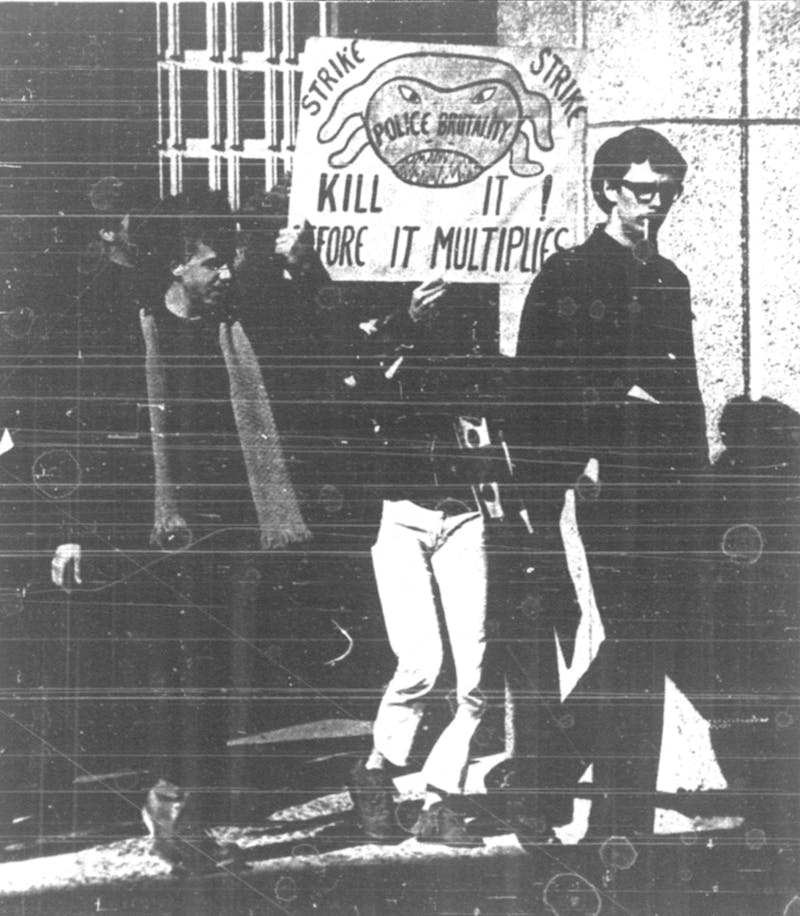

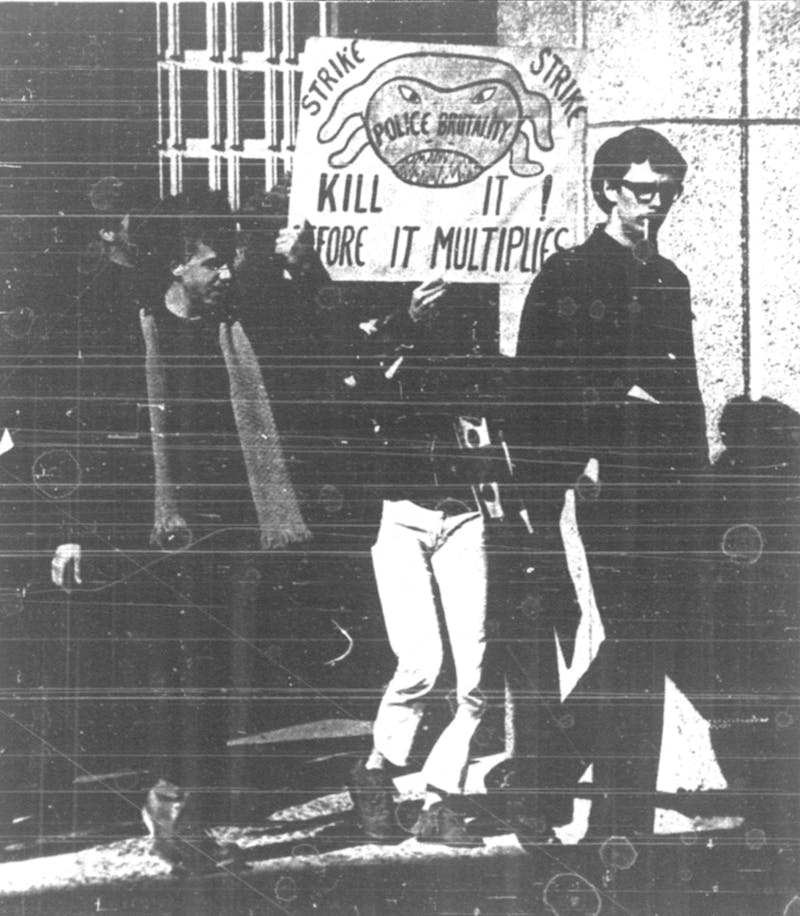

Amid the anti-war movement of the 1960s, UW-Madison students and faculty channeled anger toward police brutality through art.

Warrington Colescott, professor emeritus of printmaking and painting at UW-Madison, created a piece in 1969 called “Out of a Garden Window” while teaching. Colescott depicts a protester being beaten and arrested by police, with other protesters being corralled away and an audience forming in front of their suburban houses. It is thought to be directly inspired by the anti-Vietnam war protests on campus.

This piece appeared as part of a 2018 exhibit “Print in Protest” at the Chazen, highlighting the role of UW-Madison’s printmaking department in the school’s history of protest.

Decades later, during the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020, murals in Madison and nationwide commemorated victims of police brutality and called for change. Both officially commissioned murals from the city of Madison and solo graffiti were found on walls and boarded up windows all across town.

Colescott’s piece reflects both the attitudes of yesterday as well as today. His art is timeless, demonstrating the longevity of anti-police brutality action and activism

Aside from visual art, protest can also be created for the other senses, such as music and spoken word.

In Madison, the Forward! Marching Band, founded during the Act 10 protests, spent weeks playing around the Capitol in protest. Since then, the group has “dedicated itself to maintaining that unique fighting spirit of the Wisconsin protest movement.”

During the #TheRealUW movement in 2016, UW students, alumni and faculty of color rebuked the racism they had been subjected to while students at UW-Madison, a one-day-only exhibit was held at the Chazen called “Unhood Yourself: The Real UW.”

“It will be impossible to ignore the energy and passion that each of the artists bring to the Chazen,” the exhibit’s press release read. “Here, they will live in expression and present the truth. Without veils, without anonymity, unhooded.”

In addition to spoken word performances, this exhibit included photography and collages from students who led the movement online, meant to “engulf” students in the day-to-day experience of their classmates of color.

Recently, specific iconography and phrases, often in support of the pro-Palestine movement, on protest banners have become subject to confiscation by law enforcement officials.

And, with the recent implementation of UW-Madison’s “expressive activity” policy, protest art may be in danger, at least while 25 feet from a campus building.

Yet, some fight to keep this tradition alive. The Division of Arts administers an artivism grant for students who demonstrate an interest in activism through art. In the 2022-2023 school year, the grant funded 12 projects using a total of $12,400 and plans to reopen applications for the current school year later in the semester.

Student publication the Madison Journal of Literary Criticism has been a recipient of this grant multiple times. Editor-in-Chief Landis Varughese told The Daily Cardinal the effects of artivism, including the experiences and art of Palestinians during Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza, is crucial to social change.

“[Art] makes entry points to activism much more accessible because people may not be really inclined to read dense theory about political activism,” Varughese said. “For people who are halfway around the world, who may not be able to fully comprehend [the Palestinians’] strife firsthand, the way that they can be able to have a glimpse into their world for even just for a second through art is really powerful. And it's able to show us that we aren't so distant, after all.”