Elections for The Daily Cardinal during the 20th century offer a picture into campus prejudices and contemporary social movements.

Over the past 134 years on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus, The Daily Cardinal has covered 34 presidential elections, countless campus and statewide referendums and races for multiple student governments.

These elections have taken place in the shadow of world wars and counter-culture movements, but the best bellwether for the mood of campus and the national climate has often been elections for control of the Cardinal itself.

Founded in 1892, the Cardinal owes its start to a vote of the student body. William Wesley Young, the Cardinal’s founder and first editor, convened a campus vote to decide if UW-Madison should have a daily student publication, and students elected the first staff before the paper was published.

As Young originally conceived it, UW-Madison students would control the paper, which would be financially and editorially independent from the university, through direct participation, and later, campus elections.

‘Part of a national phenomenon’

In the early 20th century, the Cardinal covered a campus under transformation. The overall campus population, roughly 1,000 students in 1892, had grown to about 11,000 in 1938, in part due to increasing numbers of out-of-state students.

Many Wisconsinites felt “their” university was under threat, an anxiety manifested in “vicious” campus elections for that year.

“Splits had developed between candidates who belonged to fraternities and sororities, traditional bastions of Midwestern conservatism, and those who did not,” wrote former Cardinal Editor-in-Chief Allison Sansone in "It Doesn’t End With Us,” a history of The Daily Cardinal. “All-frat slates bested long standing liberal leaders in student government, literary societies and the Cardinal.”

At the time, a Board of Control — five students elected by the student body — approved major financial decisions and approved staff appointments. In the spring of 1938, the three open board seats were won by well-connected “fratmen,” who promptly fired Richard Davis, the editor-in-chief, on his second day on the job. Justifying the dismissal, a new board member said Davis, a Jewish student from New York, had “the wrong parents.” Another board member said “Langdon Street doesn’t want another Jewish editor.”

“[It] was a very clear-cut case of blatant antisemitism and a bunch of people who felt like they were not being covered in the manner they deserved, and so they were going to do something about it by firing this editor because he was Jewish,” Sansone told the Cardinal.

The day after his removal, 52 Cardinal staff members went on strike protesting Davis’ “dismissal without cause,” and over the next 28 days, control for the Cardinal was fought in the open. The striking Cardinal staff members and Davis published The Staff Daily — the “true” Cardinal, as they viewed it, while the official Cardinal attacked Davis’ Jewish identity and political beliefs in its pages, appealing to university leaders to shut the Daily down, according to Sansone.

National reporters descended on Madison to cover the conflict, which The Cap Times opined was “part of a national phenomenon” of antisemitism on college campuses and a “manifestation” of the “race prejudice [that] has been slinking undercover at the university” for many years.

The student government set an election date to resolve the dispute, and on May 26, 1938, more than 5,000 students — the largest turnout in campus election history — voted to keep the current Board. Davis lost by 81 votes.

“The election had become a referendum on who had charge of the University of Wisconsin campus,” Sansone wrote.

In the aftermath of the election, the Cardinal made changes to its bylaws to prevent such situations from arising again. Three faculty members, appointed by the chancellor, had sat on the Cardinal Board alongside elected students in a non-voting advisory capacity; now, they were granted veto power over any financial decisions made by the staff or student Board members, a decision that set the stage for future conflict.

Bombings, strikes and coups

The decades that followed would bring divisive national issues to the forefront of campus life and the pages of the Cardinal. During the Vietnam War, the paper embraced its critics' labels of “radical,” and editorialized in favor of campus protests.

Shortly before the beginning of the 1970 fall semester, four students bombed Sterling Hall to destroy the Army Mathematics Research Center housed within. The bomb killed one researcher, and after a massive manhunt three of the four students were caught, including David Fine, a Cardinal editor.

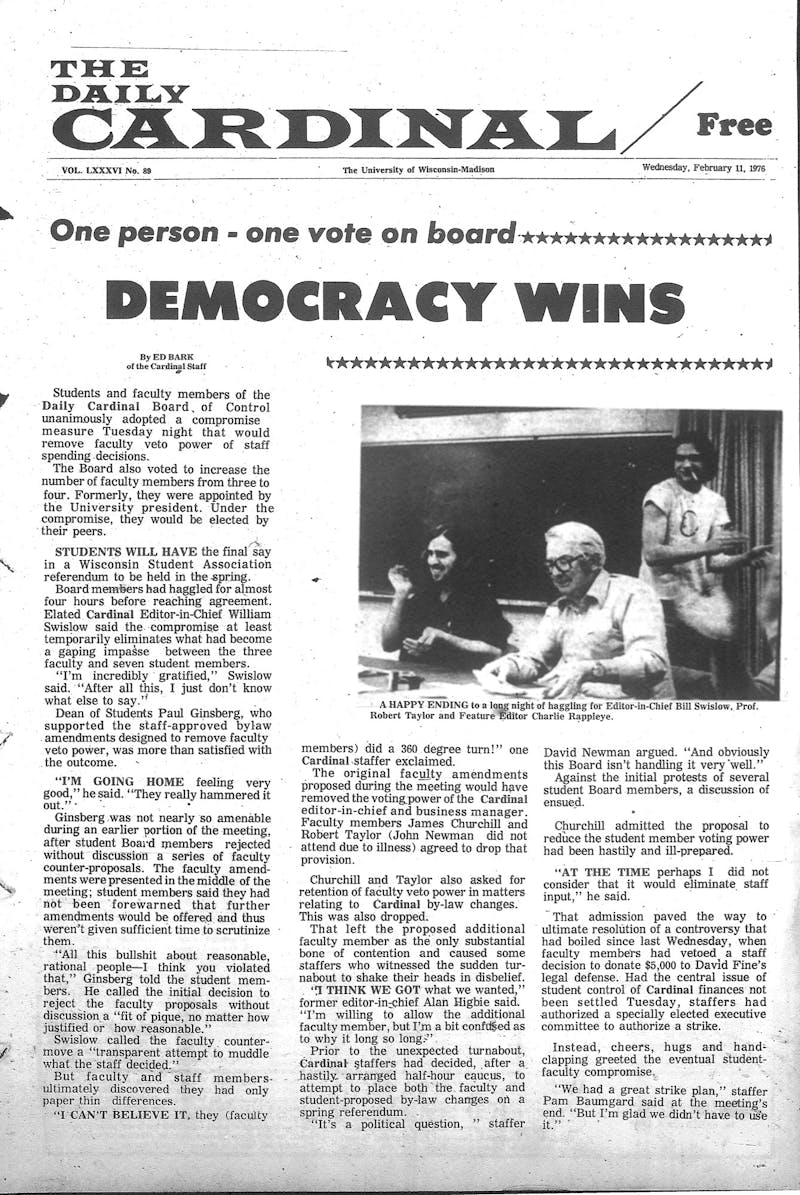

After staff elected Bill Swizlow as editor-in-chief in January 1976 he faced the question of a monetary donation for Fine’s defense, whose trial was later that year.

The Cardinal had received considerable backlash after defending Fine in 1970 and the announcement on Jan. 27 the Cardinal would donate $5000 to his defense reopened a wound on campus. Letters poured in from students and faculty condemning the decision.

The donation, decided by a vote of the Cardinal staff, had to be approved by the Cardinal Board, but since the Davis strike, the Board had rarely overruled staff decisions. But the Board, cognizant of the campus climate, rejected the donation. All but one student member of the board voted to approve the donation, but the faculty veto was unanimous.

To avert a strike from the furious staff, Swislow and the Board agreed to put a proposal eliminating the faculty veto and returning hiring and firing decisions to the student members of the board exclusively on the Spring 1976 election ballots, where board seats were also available.

The Cardinal’s continued support of Fine put the campus at odds with a campus community looking to put the Vietnam War era behind it and certain students saw the election as a chance to rein in what they saw as the Cardinal’s activism. In the largest turnout for an election in over half a decade, three students with no connection to the Cardinal — who ran on a platform of “straight journalism” — bested current and former staff, gaining a majority on the Cardinal Board.

Using powers granted by the passed referendum, the three students fired the summer editors elected by the Cardinal staff, and when Swizlow said he would perform their job, they fired him and the business manager.

“The election was a concensus [sic] of where the people are at,” a board member said. “People don’t like the paper.”

Swizlow, the other fired editors and their staff went on strike, publishing The Staff Cardinal while the Board struggled to produce the “official” paper. Ultimately, the new board members would resign and Fine never received his donation, though the saga served as an illustration of a campus recoiling from the radical years of the 1960s.

“Direct elections of student reps [were] abused [by] politicking by various campus factions,” commented a former editor after the election.

One of those factions — conservative students — founded The Badger Herald in 1969 as an alternative to the Cardinal’s left-wing “demagoguery,” and in 1987 the Herald publisher seized control of the Cardinal after winning a majority of seats on the Board for himself and his friends. He promptly fired the editor-in-chief and the business manager, seeking to consolidate the Cardinal under the Herald’s leadership.

Faculty members of the board defeated the two-week coup by dissolving the Cardinal and immediately incorporating a new Board not elected by the student body. Democracy at the Cardinal, which had allowed a near-complete takeover from a rival, was put on pause.

Today, the Cardinal Board is still elected, but there are no designated student seats anymore, nor elections that involve campus.

Sansone said those elections were a holdover from the Cardinal’s founding, where it was designed to “forge a connection” between campus and its newspaper. She said it was removed because it had become a “security flaw.”

“You don't allow people to continue to come in and manipulate you through this mechanism,” Sansone said, though she doesn’t think the Cardinal is any less democratic than it used to be. “This paper has always been what its staff made it.”

Reporting contributed by Allison Sansone