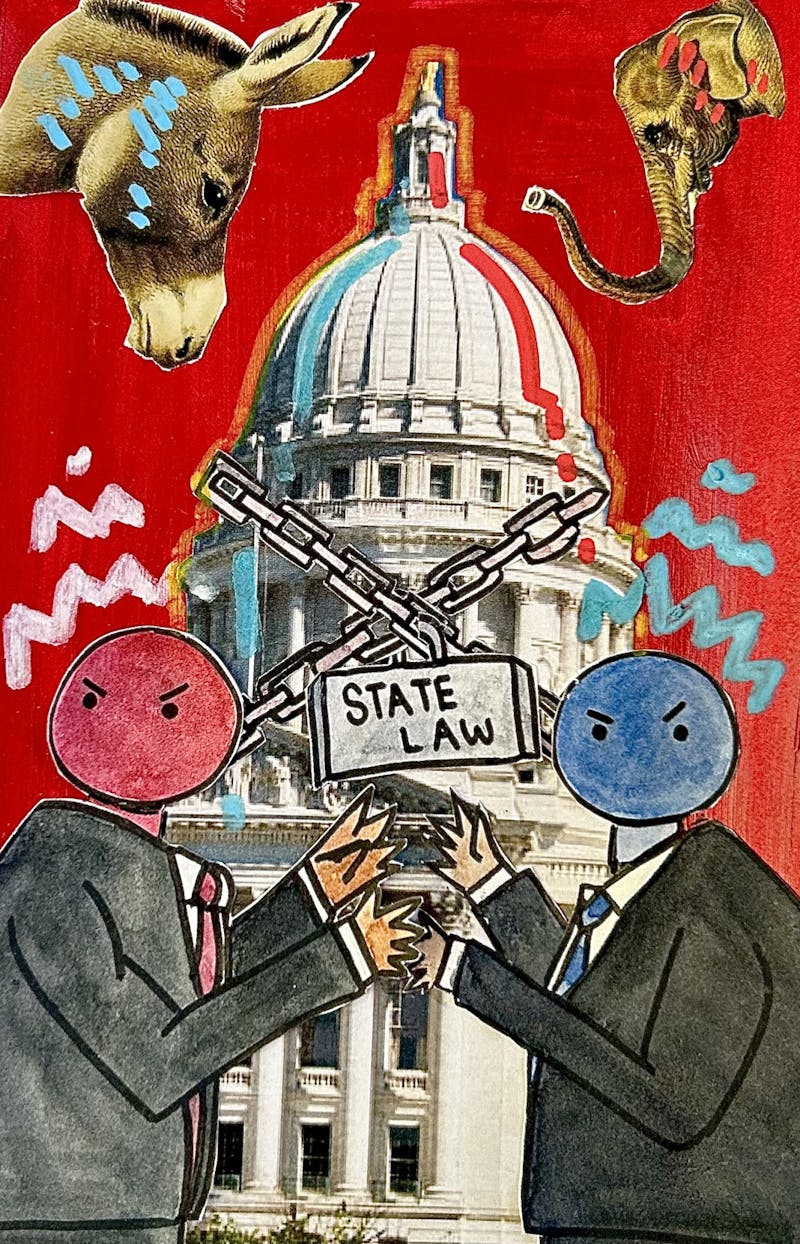

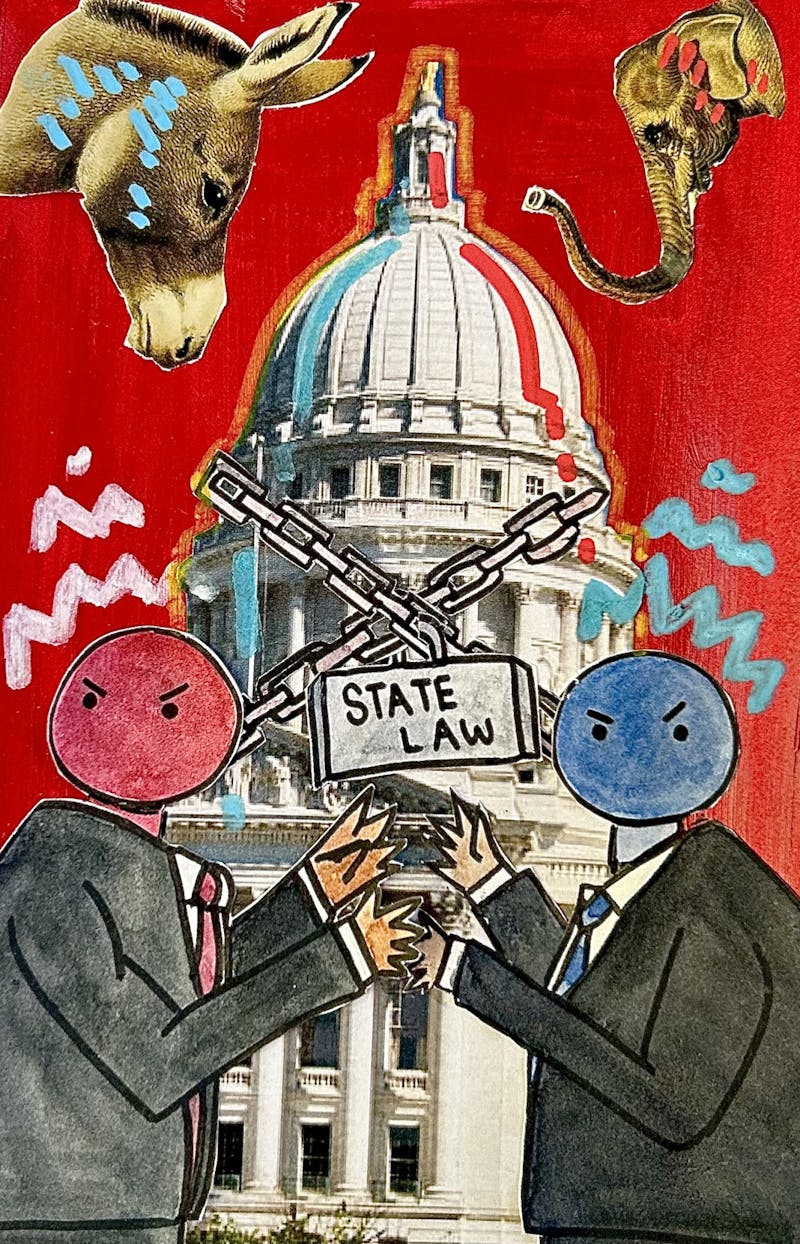

From limits on property tax increases to a near-statewide ban on local sales taxes, municipalities in Wisconsin have few options to bring in more revenue as service costs rise.

As inflation has driven up the cost of services, Wisconsin’s local governments, including the city of Madison, find themselves constrained by state laws limiting how they can raise money.

District 8 Ald. MGR Govindarajan told The Daily Cardinal that current state budgets and tax laws dating back to former Gov. Scott Walker’s administration have made it harder for Madison to provide residents with essential services.

“[City employees] haven’t always gotten the pay increases relative to inflation that they have deserved,” Govindarajan said. “The city has grown quite a lot since 2012, but we’re still at the same levels of service for trash collection, for example.”

Despite these constraints, Govindarajan and other officials stressed that city leaders have not given up in their pursuit of increased benefits for Madison residents.

GOP-controlled Legislature strikes down budgetary proposals

Madison Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway held a press conference Oct. 3 at the Madison Public Library with state lawmakers to demand greater funding for Dane County cities.

Gov. Tony Evers’ 2023-25 budget proposal included a shared revenue distribution that would make the state give to municipalities a minimum of 95% of what they gave the previous year.

Additionally, the proposal included a 5% increase in state payments for municipal services like police, waste disposal and utilities and a 4% increase in general transportation aids for both counties and municipalities.

But the biennial budget passed by the Legislature did not include these increases in funding for shared revenue, leaving Dane County cities underfunded.

This is a result of 2023 Act 12, which initially intended to give all municipalities more funding but has created a disparity between Madison and the rest of the state.

City Communications Manager Dylan Brogan told the Cardinal Act 12 has changed “very little” in what Madison can achieve through state funds despite the fact that Madison has added 90,000 residents since 2000 and is the fastest-growing city in the state.

“That’s a lot more people paying state sales and income tax — a portion of which is supposed to help fund local governments,” Brogan said. “In 2024, Madison receives just $29 per resident through the shared revenue program. The average for Wisconsin cities is $195.”

One particular impact of the shared revenue overhaul is that underfunded communities can begin to see cuts in the availability of important services, such as fire departments.

Another impact of shared revenue decreasing is that it becomes harder for governments to hire public defenders and district attorneys at competitive salaries, according to Wisconsin Public Radio. This leads to a growing number of backlogged cases accumulating in the court system.

Evers had previously pushed for a raise for public defenders and assistant DAs in his budget proposal before Republicans cut it.

Raising revenues in municipalities is often difficult

Beyond shared revenue from the state, a large part of Madison’s budget is funded by levying taxes. An estimated 71% of the city’s annual revenue comes through property taxes.

“How the state government expects local governments to fund themselves is through the property tax,” Govindarajan said. “If local municipalities want to raise their budget, they are basically forced to ask taxpayers to increase their own taxes in order to pay for city services.”

Wisconsin used to rely heavily on income and property taxes as a part of its revenue stream until the election of Walker in 2010 signaled a shift to fiscal conservatism and tax cuts. The cuts amounted to a 4.4% per capita reduction and created negative externalities for cities.

“Walker basically cut aid to local governments and then also their ability to raise revenue,” Brogan said. “You used to be able to raise property taxes based on inflation and net new construction. Well, he took off the inflation part.”

The Legislature’s budget-writing committee’s May 2011 legislation on property tax levy limits changed the minimum levy increase for inflation from 3% to 0%, prohibiting municipalities from increasing their base levies by more than one percentage that exceeded the local government’s total value of all taxable property.

While the introduction of levy limits was a response to a then-contemporary growth in municipal tax rates, the loss of these minimum limits on levies has led to low-growth municipalities being unable to keep pace with inflation, according to the Wisconsin Policy Forum, a nonpartisan policy research organization.

Brogan underscored the city of Monona’s Nov. 5 referendum on instituting a one-time $3 million increase to its property tax levy as an example of a city struggling to keep up with costs. The 2024 Wisconsin Department of Revenue report found that Monona’s levy limit is only 0.45%.

“How in the world are they going to be able to keep up with those costs when their ability to raise the property tax levy can never keep up?” Brogan said. “That’s something that hopefully the state Legislature is going to be addressing at some point, and that just is the tip of the iceberg of the revenue restrictions.”

In his 2023-25 budget proposal, Evers suggested allowing municipalities greater privilege with selecting their own sales tax — known as the local option sales tax — giving Milwaukee County the ability to impose an additional 1% and other counties an additional 0.5% to their base.

But the budget passed does not contain these measures.

Rhodes-Conway named a local sales tax option as one of the items that would help Dane County communities secure the funds necessary to avoid cutting services during her Oct. 3 press conference.

Partisan divides and next steps for cities

When the biennial budget passed in 2023, Democrats unilaterally objected to it with no party members voting in support. One provision that Democrats took issue with was the institution of a tax cut when the state was in possession of a $7 billion budget surplus.

“Republicans have been in charge of the Legislature for 14 years now,” Brogan told the Cardinal. “Gov. Evers has proposed budgets that treat cities like Madison a lot better, but the Republicans just ripped that up and passed their own budget.”

To combat a budget shortfall, the Nov. 5 election in Madison will feature a $22 million funding referendum on the ballot to increase the city’s property tax levy above state levels.

“We specifically came up with that number because that’s what it takes for us to continue our services,” Govindarajan said. “If the referendum passes, we’re not adding anything new. If we do not get that $22 million, we have to cut services.”