How do you measure poverty? It depends on who you ask. Poverty expert Timothy Smeeding and WISCAP Executive Director Brad Paul explain how policies designed to fight poverty work behind-the-scenes.

Image By: Lily Houtman

How do you measure poverty? It depends on who you ask. Poverty expert Timothy Smeeding and WISCAP Executive Director Brad Paul explain how policies designed to fight poverty work behind-the-scenes.

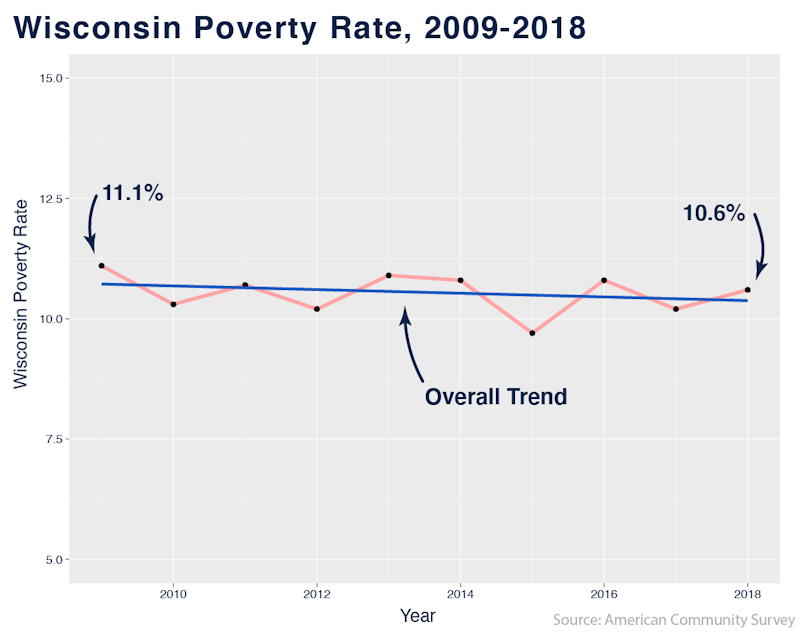

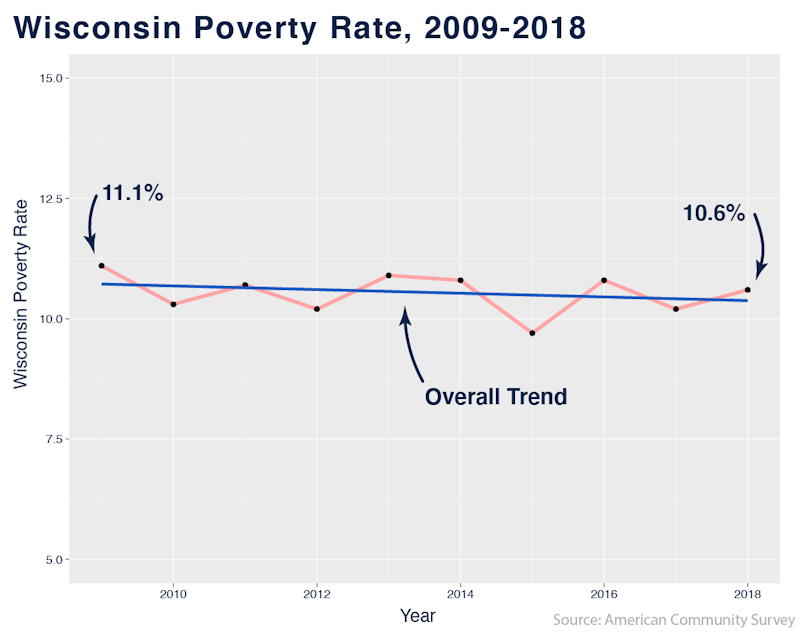

Image By: Lily HoutmanThe most recent report from the Institute for Research on Poverty at UW-Madison, published in October 2020, showed 10.6 percent of Wisconsinites lived in poverty in 2018. That rate has not changed much from 11.1 percent in 2009, when the state was beginning to recover from the Great Recession.

Before lawmakers attempt to fight poverty with policy, researchers have to develop an accurate measure of poverty in the state. There are multiple ways to measure and understand poverty, depending on who you ask.

How do you measure poverty?

Researchers at the Institute for Research on Poverty (IRP) developed the Wisconsin Poverty Measure (WPM), which takes family income and public cash benefits into account, adds noncash benefits like FoodShare and tax credits and adjusts for geographic differences in prices.

Timothy Smeeding is an expert on poverty and economic mobility and the former director of the IRP. He explained why the WPM provides a more holistic picture of poverty in the state rather than looking only at income.

“We adjust for the fact that the cost in Wisconsin is only about 90 percent of the cost of living in the country. And then within Wisconsin we adjust for the fact that living in Milwaukee [or] Madison is much more expensive than living in Bayfield or anything up in the northwest part of the state,” Smeeding explained.

There are other ways to measure poverty, including the market income poverty measure — which only includes income — and the Census Bureau’s official poverty measure, which takes into account public cash benefits.

The measures offer different pictures of poverty, but “overall trends in poverty according to the three measures are similar over the last several years, until 2018,” according to the report.

In 2018, the IRP’s poverty threshold for a two-child, two-adult family was $27,904. Using the WPM, researchers determined that the state poverty rate was 10.6 percent, continuing an increase since 2015 when poverty hit its lowest point since the Great Recession.

The IRP has not yet studied poverty in 2019 and 2020 due to the pandemic. The report noted that the pandemic has included “historic rates of unemployment and closure of schools and child-care facilities, but also significant intervention by the federal government spending trillions of dollars to stabilize the economy.”

“In 2020, poverty will probably be higher. In 2021, poverty should go back down, we hope,” Smeeding said. “It’s a strange economy and it’s a strange recession. The last recession was more widespread, it wasn’t quite as steep. This particular recession particularly hit women and minorities.”

What impacts poverty?

Beyond measuring the scope of poverty in Wisconsin, the IRP also uses the WPM to research how benefits and expenses affect poverty. Anti-poverty policies like tax credits, food stamps, housing programs and energy assistance led to a drop in poverty, while increasing costs like out-of-pocket medical expenses push more people into poverty.

In 2018, there was a shrinking effect of the Earned Income Tax Credit, a tax break for low- to middle-income workers and families. Still, FoodShare had a larger impact on reducing poverty compared to 2017.

On the other hand, costs like work expenses, including child care and medical expenses paid out-of-pocket rose in 2018. Medical expenses have a large influence on elderly poverty rates in Wisconsin, which rose from 2015 to sit at 9.7 percent in 2018.

“Higher medical out-of-pocket expenses means you have less money to spend on other things you need, so that makes poverty go up. Higher costs of going to work, including child care and commuting costs, means you have less [money] after,” Smeeding explained. “If you subsidize child care more or we took the Medicaid expansion, we’d end up reducing poverty because people would need to spend less on those things, particularly elderly people and disabled people and mothers with kids.”

Where does poverty exist in Wisconsin?

In 2018, 15 counties in the east central region of the state had poverty rates below the state average of 10.6. Fifty-five counties, including Dane, did not have a statistical difference from the state average.

However, Milwaukee and Racine counties are higher than the state poverty rate, a trend that has been consistent throughout the IRP’s research. Milwaukee County’s poverty rate was 16.2 percent and Racine county’s rate was 14.2 percent in 2018.

“The variance of poverty within Milwaukee County is much higher than the variance between Milwaukee county and the rest of the state,” Smeeding explained.

According to the report, the poverty rates within the county ranged from 6.9 percent in the western part of the county to 31.6 in the central city of Milwaukee, “suggesting significant economic segregation” within the county.

How does research support public policy?

After researchers like the IRP’s determine the scope of poverty in the state, policymakers and advocacy groups can use the research to develop policies to fight poverty in the state.

The IRP continues the long-standing Wisconsin Idea, which describes how university experts worked with the state government in the early 20th Century to develop innovative legislation.

The IRP’s annual report is supported by the Wisconsin Community Action Program Association (WISCAP), which represents local community action agencies that provide services to low-income individuals. WISCAP advocates for public policies affecting people in poverty at the local, state and federal level.

WISCAP Executive Director Brad Paul, who has developed anti-poverty legislation at the federal level, explained that the IRP and WISCAP are like “cousins” because the IRP informs WISCAP’s policy.

“The main reason [the report] is valuable for us is that it includes the value of benefits in one’s household income. Why that’s important is it shows that anti-poverty programs and benefits can help lift someone out of poverty,” Paul explained. “Your typical federal poverty measure doesn’t do that. For us, as an advocacy organization, it’s valuable for us to point to that and say, ‘See, this is how it’s helpful that we’re investing in robust public benefit programs.’”

Among other policies, WISCAP supports expanding broadband, the availability and affordability of childcare and Medicaid in Wisconsin. They also have introduced their own comprehensive legislation designed to fight poverty in Wisconsin.

How do policymakers and advocates develop policies that fight poverty?

In the 2019 legislative session, WISCAP worked with lawmakers — including Sen. LaTonya Johnson, D-Milwaukee, and Rep. Lisa Subeck, D-Madison — to introduce the Wisconsin Opportunity Act. The bill was introduced by 18 representatives and co-sponsored by six senators.

The bill was referred to a committee in October 2019, but never passed through either chamber. The pandemic put all legislative activity on hold in March 2020. Paul said WISCAP is planning to reintroduce the bill in April with some changes.

“This is the blueprint you need to fight poverty in Wisconsin. It includes housing provisions, access to health provisions, job and income supports and transportation,” Paul said. “It’s all of the things that [community action agencies] see on a daily basis, the needs of those folks who come through their door, expressed through legislative language…It’s a multi-pronged approach.”

Paul explained that aspects of the large package, called an omnibus bill, could also move forward as standalone bills. The 2019 bill would have increased funding for housing grants, community action agencies and mass transit systems, among other provisions.

The bill would require the Wisconsin Housing and Economic Development Authority to issue a report to the legislature on the number of households in “worst case housing," as defined by the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. It would also require the Department of Public Instruction to report the number of homeless children in public schools to the legislature each year.

“I’m not convinced lawmakers are all fully aware of the extent of the problem. So we’re asking that the data that they get every year through DPI through the districts [is] required to be reported out to the legislature, so it doesn’t stay just within DPI or those of us who know about it,” Paul said. “That’s how policy gets made, is education and knowledge. So we think that’s significant even though it’s not a big [fiscal] item.”

WISCAP has focused on the housing crisis during the pandemic, which presented danger for a wave of evictions. Paul said that when the state received CARES Act funding, Gov. Tony Evers dedicated $25 million to rental assistance, which was funneled through the WISCAP network. Over 14,000 households were served in every county.

“That’s [been] all-consuming, all-hands-on-deck for that, both at the local and what we’re doing at the state level in terms of policy and the programs and the coordination and all of that,” Paul said. “It took COVID, but we’re finally getting a really important discussion around the safety net and what people need to be economically stable.”

Where do we go from here?

Both Smeeding and Paul discussed the impact of the federal government’s new American Rescue Plan, which includes anti-poverty programs like the child tax credit, which could have a profound impact on reducing child poverty.

Under the new legislation, the child tax credit increased to $3,000 for children ages 6 to 17 and $3,600 for children over 6. The amount is gradually reduced for couples earning above certain income brackets. Eligible families will get payments up to $300 per child per month from July to the end of the 2021, according to NPR.

Smeeding said that in future IRP poverty reports, researchers will be able to estimate the effect of the child tax credit, which should have a “big effect on child poverty in Wisconsin.” The child poverty rate in Wisconsin was 11.1 percent in 2018 compared to about 14.4 percent nationwide.

Paul said he was amazed at the “New Deal style” of the new legislation, and said that WISCAP’s agencies will see a positive impact and be able to “meet the needs of people in their communities.”

“How this happened is wild,” Paul said. “We’re about to see a sea change in how people view the role of government in tough times. I think we’re at a really pivotal moment, and it gives me hope.”